As I begin to write this post, you can probably figure out where I’m going with it. I’m conservative and I’m from Arizona; predictably, I hate the new Babylon that is California with a xenophobic passion that rivals a stomped ant nest.

I think it’s reasonable to assume I wouldn’t write this article at all if in the end it turned out there actually wasn’t any problem and that the issues were the invention of a crazed right-wing media machine.

While that might be right (we all have our biases, and I do love my gotchas) there’s actually a third option: I have no idea what’s going on here.

I briefly skimmed Applied Divinity Study’s article yesterday, which you should probably go read for context and to make sure I’m not misrepresenting it. The short summary is that ADS believes that many aspects of the popular story are misleading. For instance, he says that the limits on the amount shoplifted that trigger a felony are similar or higher in other states (and thus prop 47 isn’t even unusual) and that most of the links between prop 47 and higher crime are wrong for one reason or another.

He concludes from this and other points that the shoplifting epidemic is mostly made up; it’s a pretend thing we bought whole-cloth because it’s an attractive story, rather than any compelling data proving it.

While it struck me as suspicious, I don’t have any particularly great reason to disbelieve it besides previously having accepted as true the idea that California was experiencing problems with shoplifting as a result of lax sentencing laws. Don’t get me wrong; I’d still find it deeply psychologically satisfying if this were so, since it would confirm a lot of my biases. But I figure it’s at least worth knowing if I’ve been misled, so here we go.

(Note: I don’t know ADS’ sex. I’m defaulting to “he” here, because it’s easier than trying to balance a bunch of “they”; I’ll update later if I get better data.)

Argument 1: “Forget the empirics for a second, and just look at the actual policies. California’s Prop 47 decriminalises shoplifting and means that there are no consequences for criminals. That’s clearly bad right?”

ADS says it’s not really that odd that California has a floor on how much you have to steal before you might face prison time and a felony record. He points out that a lot of states have one, and that some states actually set that floor much higher:

Similarly, in an article tilted 'San Francisco Has Become a Shoplifter’s Paradise" the Wall Street Journal argues:

Much of this lawlessness can be linked to Proposition 47, a California ballot initiative passed in 2014, under which theft of less than $950 in goods is treated as a nonviolent misdemeanor and rarely prosecuted.

That sounds really bad right? It would be horrible if San Francisco were experiencing an entirely avoidable crime spree due entirely to some ridiculously misguided progressive policy.

…Except that this causal attribution is not even plausibly correct.

Though it’s tempting to frame the law as just another artefact of California’s bleeding-heart progressivism, similar laws are in fact present in all 50 states.

You might object that other states have different financial thresholds for felonies… which would be a good counter argument except that California is actually on the low end. Every single US state has a minimum threshold for felony theft, and 38 of them are higher than California’s. Texas notably has a threshold of $2500, which means you can steal 2.6 more than you could in California before being classified as a felon. Talk about incentives! [1]

The footnote there goes on to talk about how most of these limits aren’t keyed to inflation, so arguably they are in a practical sense much lower floors (and thus stricter) than when the laws were enacted.

To see how right he is about this claim, we have to look at two things: first, laws are pretty complex. Prop 47’s numerical value might be a little different, but it doesn’t exist in a vacuum devoid of other laws; it’s possible that in the grand ecosystem of laws the practical effect of the limit is different from one system to another.

Taking a look at Texas, which ADS singled out, we immediately fine one pretty big difference in what Texas considers a felony:

(D) the value of the property stolen is less than $2,500 and the defendant has been previously convicted two or more times of any grade of theft;

Whoops! Texas has a three strikes law. So while their floor is pretty high, if they’ve been caught stealing bubblegum twice and convicted that third pack of Bazooka Joe still costs dearly.

This doesn’t mean we immediately can discount the rest of the article, but it means we have to look pretty closely at every stat, because between “I’m on theft number 3, and going to prison” is not insignificant to the point where you can just compare value-of-theft floors and give people the whole picture of what’s going on. So when ADS looks at this claim:

Argument 1: “Forget the empirics for a second, and just look at the actual policies. California’s Prop 47 decriminalises shoplifting and means that there are no consequences for criminals. That’s clearly bad right?”

and comes to this conclusion:

But this first one is easy. It’s not even arguable. It’s just poor causal attribution, poor reasoning, and an abject failure to do even the bare minimum of background research before reporting in prestige media outlets.

He’s not even technically-best-kind-of-correct correct, because he didn’t address anything like the entire space these laws exist in. He’s not necessarily wrong; it absolutely could be that this is too small of a change to matter. But ADS is using this section to say something close to “This limit couldn’t matter, because similar limits exist” without looking at any cofactors at all.

A theoretical person who is willing to tolerate unlimited misdemeanor charges but fears a felony isn’t unimaginable here, and realistically could fear the consequences of shoplifting Texas in a way he doesn’t in California, misdemeanor dollar-value limits be damned.

I now have to sort of assess the rest of the claims suspiciously; again, this isn’t wrong. It’s not uninteresting. But it also doesn’t prove nearly as much as is claimed here.

Argument 2: “San Francisco has a shoplifting surge, but it’s not reported because people know the police won’t respond, and the new DA won’t press charges.”

This one is pretty easy, I think. ADS says that the source of the crime wave (should it exist) couldn’t be that the DA doesn’t prosecute crime or that the cops don’t respond to calls related to shoplifting, because if it were so he’d be able to track it in data from neighboring counties:

Imagine you’re an organised criminal in the Bay Area, but not living in San Francisco proper. Perhaps you’re across the Golden Gate Bridge in Sausalito, or across the Bay Bridge in Oakland. One day, San Francisco elects a new District Attorney who’s famously soft on crime and refuses to prosecute shoplifters. Do you:

A) Continue to shoplift in Oakland where you might be caught and punished, or

B) Take a 15 minute BART ride to San Francisco where you can shoplift with impunity?

In other words, if San Francisco is truly the “shoplifter’s paradise” its critics claim, we shouldn’t just expect to see a rise in cases locally, we should expect a drop in cases in all of its neighbours. Shoplifters should be virtually swarming from across county lines to partake in the unencumbered criminality.

He then says, look, shoplifting crime didn’t fall very much in neighboring counties:

It’s tricky, cases do fall, but most of that is pandemic effects. When compared to the state as a whole, adjacent counties saw relatively little decrease in shoplifting (with the slim exception of San Mateo). That’s the exact opposite of what you would expect to see if criminals were following their alleged incentives.

Faced with the San Francisco data alone, you might argue that residents have given up on the DA, so reports are down even as crime is up. But it’s hard to tell a similar story about adjacent counties’ apparent lack of reported decline.

This all sounds pretty plausible, but there’s a lot of angles to look at this from, and we are already forced to be a bit suspicious that ADS is only looking at it from one. And if you think about it for even a moment, there are a lot of alternative assumptions you could make that end with SF’s crime rate going higher while surrounding areas don’t drop.

First, consider a hypothetical “independent” shoplifter. They aren’t part of an organized crime gang; they just steal sometimes. in ADS’ telling, it’s a given that this person would hop on public transit, commute to their shoplifting, then ride back to their local area loot-in-tow.

That, again, is possible. Are individual shoplifters likely to commute? My intuition says no; it seems to me that the average shoplifted likely isn’t the kind of person making a decision as complex as “I will board a train, commute into SFPD territory, walk to a Walgreens, shoplift a large amount of goods, walk back to a train, board again, and ride home even though the $950 limit applies to both places. I’ve heard the DA is soft".

If they did that kind of thinking, they start to get into the “I’d expect them just to have jobs at that point” range. This again doesn’t mean ADS is without question wrong - it’s a question of competing perceptions.

(Editor Nick adds: Maybe shoplifters are like everyone else, in that they don’t want to be in San Francisco a moment longer than they have to.)

ADS’ assumption seems a bit more probable to me when we consider organized crime rings. Now hypothetical shoplifter has a job of sorts; his boss is ordering him to go to SF to shoplift. It could be! But it’s also possible to have an increase in shoplifting in SF due to organized crime that happens in ways that don’t draw off other areas. A new crime ring could spring into existence; another pre-existing local ring could shift from other types of crime.

Does ADS know, somehow, that these people are commuter types, or that there aren’t practical or turf-related issues keeping crime rings from moving in from other places? He might, but if he did he didn’t explain how. Maybe there’s a study somewhere proving shoplifter mobility, but if there is I don’t know of it and ADS doesn’t share it.

The rest of the data points he uses (i.e. that crime didn’t drop in neighboring counties in a way that he doesn’t feel comfortable attributing to covid) don’t do much to prove his point as a consequence.

Again, he’s taking pieces of evidence that could mean a lot of things (or in this case, nothing) and applying it as strong evidence of one particular preferred conclusion.

Argument 3: “We know San Francisco has a shoplifting problem because stores are closing. That can’t be faked and wouldn’t happen otherwise, so it’s strong evidence that the city has a real problem.”

Argument 4: But I’ve seen the viral videos!

These two sections respectively argue that Walgreens store closures aren’t much worse than what we’d expect in a normal year and that viral videos are single anecdotal data points and thus not great evidence. I think broadly he’s right on both, so there’s not much to see here.

To the extent I’d like to quibble, I’d be tempted to point out that he only looked at Walgreens stores, as opposed to a more diverse bushel of retail outlets. But to do that, I’d have to be a bit of a hypocrite. The thing about finding data for an argument in an article like this is that it takes time that doesn’t seem relevant unless you are writing the argument. In the same situation, I’d probably only look at 1 or 2 stores myself.

Unless some easy-to-find aggregated data source exists, this kind of super-intensive research for one sub-point in an article ends up being a pain in the ass real fast with very limited rewards. Scott and Zvi are both pretty good at doing it anyway, but I suspect most people would end up just going “screw it, I just won’t write that section” rather than do an entire research project to make it work.

I think the point ADS is trying to make here is something different, anyhow. These two sections are less “here’s hard and fast data stores aren’t closing” and more “I’ve done more research on this than most, and it’s not obvious a lot of stores are closing. Anecdotal data isn’t good enough here, and I’ve cast an adequate shadow of a doubt”. Given that, I think these sections can stand without much scrutiny.

Argument 5: “Chesa Boudin really is overly progressive. He has naive views about criminal justice, and charging rates have dropped as a result. I don’t have to prove that as consequences fall, criminality goes up.”

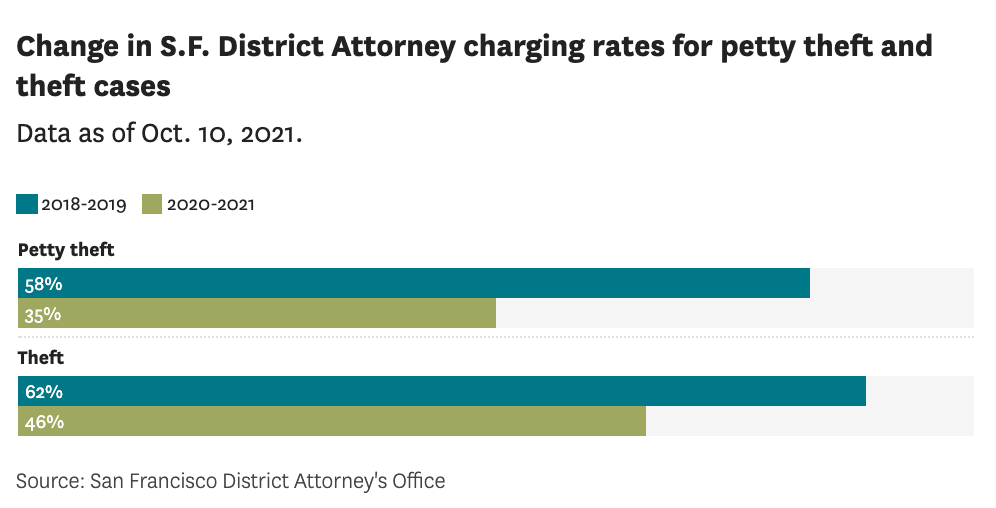

This is probably the section I feel the worst about in the whole article. There’s some stuff going on here that makes me doubt ADS as a good source on certain subjects in general, even if he’s using what superficially looks like good data. The relevant crime here is petty theft, and ADS shares the following graph and paragraph:

They have indeed dropped for theft and petty theft, and by fairly substantial levels! Petty theft in particular is down from 58% to 35%. So is that it? Despite everything, Chesa really is soft on crime, and whatever the other evidence suggests, it would be strange for this change to not result in a dramatic surge?

He’s working his way to a “but” here, but note that this is very consistent with the viewpoint he’s rebutting. It’s not proof, but if I say “listen, man, I think the problem here is that the DA is soft on a particular type of crime”, the first thing we do is check to see if he actually is passing on prosecuting cases. If we find that he got into office and prosecuted about 40% less than the last guy, we can argue how strong of evidence that is, but not that it’s evidence at all.

ADS did at least acknowledge in passing that this reduction doesn’t mean literally nothing, but then things get a little tricker:

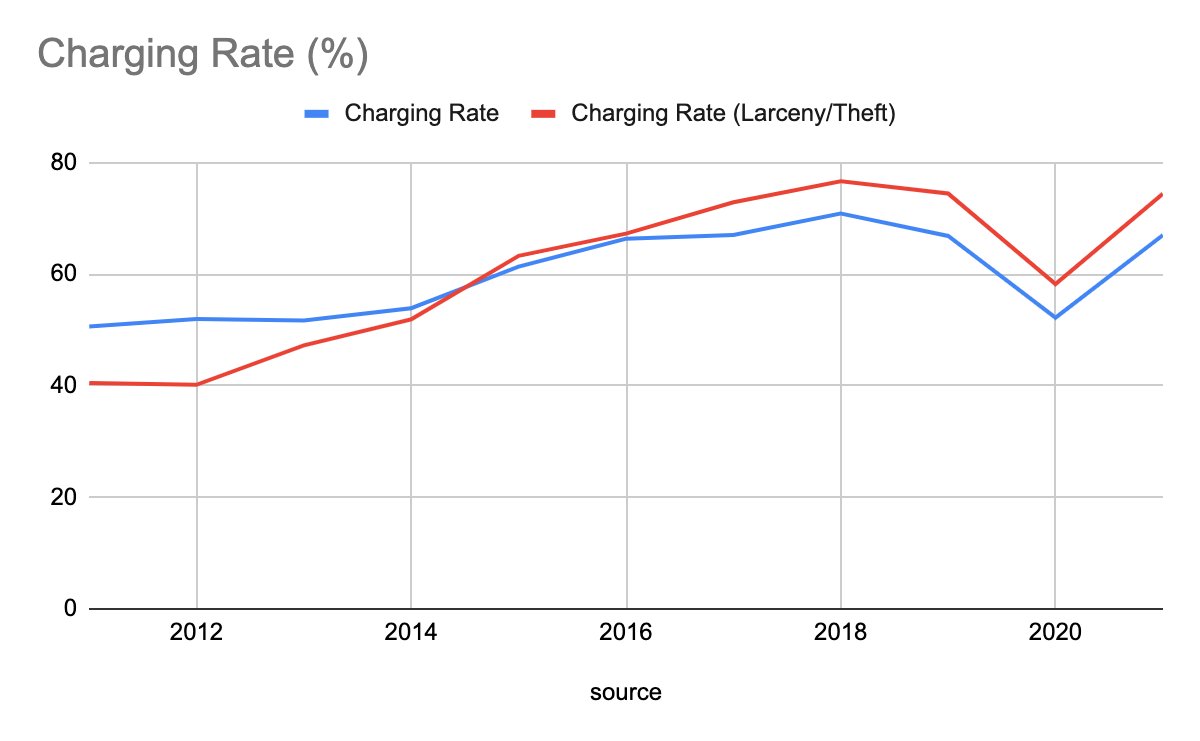

Not so fast. Again, we have to understand the results in context. Here are charging rates for Chesa and the previous DA over the last decade, both overall and for larceny/theft:

There was indeed a sharp drop in 2020, but it was followed by a sharp uptick. For Larceny/Theft, the 2021 rate is still a bit under peak (74% versus 77%), but much higher than the historical average of 61%. His overall 2021 charging rates are even more aggressive, coming in just under the 2018 peak (67% versus 71%), and much higher than the average of 60%.

In both cases, Chesa’s 2021 rates are higher than those in 7 out of the 9 years preceding his tenure.

Note the shift from “petty theft”, the sub-$950 theft we care about in this discussion, to “larceny/theft”, a broader category that catches all of what we care about in a discussion about shoplifting plus a lot of stuff we don’t care about at all. You might question why this chart is here when more specific information is available; so do I.

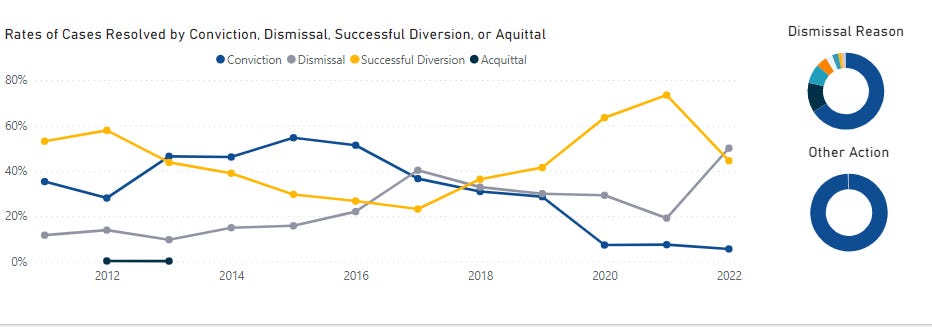

His source for this data point is this site. If we go there and ask “How many people actually faced some form of music for petty theft?”, which is probably the most relevant question to the “is Boudin soft on crime” discussion, you get this:

If we are charitable and only look at 2018 here, we find there were 80 cases that got punished in some way or another - jail time, fines, etc. in 2020, Boudin’s “most punished” year, only 19 people got punished. Arrests for the same crime were 220 in 2018, and 105 in 2020. So with ~48% of the arrests, Boudin convicted about 24% of the people.

Best case scenario, Boudin is about half as likely to actually punish any given petty theft arrest he’s presented with. If we look at 2021 instead of 2020, that drops to 18%.

If I’m right that ADS used the wrong crime category above (though the right one was available) and that he used the wrong measure of “soft on crime” (i.e. by ignoring how many people actually get punished), then statements like this are pretty hard to defend:

There was indeed a sharp drop in 2020, but it was followed by a sharp uptick. For Larceny/Theft, the 2021 rate is still a bit under peak (74% versus 77%), but much higher than the historical average of 61%. His overall 2021 charging rates are even more aggressive, coming in just under the 2018 peak (67% versus 71%), and much higher than the average of 60%.

In both cases, Chesa’s 2021 rates are higher than those in 7 out of the 9 years preceding his tenure.

(Edit 3/7: My wife has informed me I included this quote twice. I’m leaving it here because even though it’s weird to do that it’s more convenient than me making you scroll up to the last quote, and also as proof that my wife reads my articles, which means I’m famous)

The fact that last year Boudin successfully prosecuted less than a tenth of what we saw in the next lowest year in the last decade is relevant as hell here, because charging someone with a crime doesn’t mean a whole lot if they don’t actually see any punishment as a result.

So where do all those extra arrested people go? Basically, Boudin will do absolutely anything to keep a petty theft case from going to trial:

Wherever he can, he diverts the cases - i.e. no bail releases them and asks them to attend a class. Where he can’t do that, the case ends up dismissed or pled down to something lesser than the already light penalties for petty theft.

Contradicting ADS’ hints that Boudin isn’t soft on crime at all, Boudin himself doesn’t actually deny that he was. ADS points out that in late 2021 Boudin acknowledged he wasn’t doing much in the way of prosecuting, and blamed all this on COVID:

So if Chesa isn’t particularly light on crime, why the drop in 2020? Chesa’s own defence is that logistics were difficult, and he had to prioritise. From the same SF Chronicle piece:

Boudin maintains that the drop in charging rates for theft is mainly due to the reduced operation of San Francisco’s court system caused by COVID-19 restrictions. The charging rate for both types of theft increased between 2020 and 2021 as the city reopened, the data shows.

“We had clear instructions from courts to delay and defer anything we could delay and defer, [and] from the medical director to drastically reduce the (jail) population,” he said. “In the context of those really difficult decisions, we did make intentional decisions to delay or defer charging low-level nonviolent cases.”[4]

Granting his defence, we’re not left asking if Chesa’s charging rates are high enough across the board, but if, given some limited capacity to process cases, he was allocating resources in a reasonable way.

Boudin, a politician, says that none of this is his fault; there’s nothing he could do. ADS goes “OK, taking that as a given…” and proceeds to take it as a given, and says that Boudin is just prioritizing. He shows that other rates of prosecution haven’t dropped as much, so he’s just using resources efficiently.

But if that’s so and COVID is driving this, we’d expect to see him taking more cases to trial in 2021 than 2020. But that’s not the case; Boudin doubled down as restrictions got lighter and managed to not even break into double-digit conviction numbers.

Like I said, this is the worst section in the article. ADS points Boudin as reasonably hard on crime, and takes him at his word that any time he isn’t it’s because of COVID. But a simple check from the same data ADS is using shows that Boudin dismisses, diverts or pleas down to nothing almost every petty theft, and that he only did this harder and faster as COVID became a less valid excuse.

If you like diversion programs or think they are helpful, that’s fine. But handwaving accusations Boudin is soft on by ignoring most of how he actually handles shoplifting charges is disrespectful of your audience; it’s telling them hand-picked facts to make sure they don’t end up getting unapproved-of ideas. ADS is usually better than this, and I wish he had been here.

Argument 6: “Reported cases are actually skyrocketing.”

This one is sort of a non-starter for me, in the sense there’s not much to argue with here. ADS mostly rejects the idea that Boudin is soft on crime, which I disagree with for reasons I’ve already stated. Because of that, he never really addresses the idea that cops aren’t arresting people they know Boudin will just let go, and thus stores have given up on calling the cops in the first place.

Because of that, the next most relevant thing he can talk about is reported cases, which he argues aren’t that crazy out of line with historic data. I’m willing to take that as a given at this point in the article, because there’s so much else wrong here that I’d essentially be having a different argument than he is at this point.

Other stuff I don’t really know how to handle

Low shoplifting arrests

Where did all the shoplifting arrests go? Part of the huge reduction in actual meted punishments for petty theft above have to do with massively decreased arrests. ADS seems to attribute this mostly to COVID, something like “People won’t shoplift during a pandemic, or businesses were closed”.

Last July, SF Police Chief WIlliam Scott said this:

"Sadly, as it relates to crime, we've gotten a lot of negative attention," Breed added. "What is not getting the attention is the fact when you do come to San Francisco and commit a crime, you will be arrested by this department."

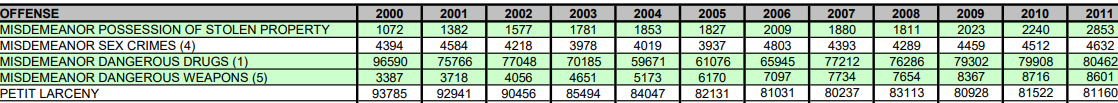

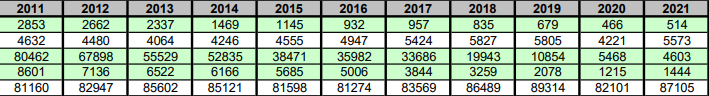

But either this isn’t true (for whatever reason!) or shoplifting basically dropped 50% overnight and persisted in being down for almost two years. Since “SF figured out the magic bullet to halve shoplifting” is a big enough story that we’d be hearing about it everywhere and SF would presumably bring it up if it were even kinda true, we can guess that’s not it. Here’s NYC’s complaint rates for the last couple decades:

The complaint rate is pretty standard across the years and is consistently in the 80000-85000 range. But filtering for 2020 vs 2019 here gives us petit larceny absolute arrest numbers of 11406 and 21627 respectively. The arrest rate dropping in an entirely different city means it’s at least plausible this isn’t a Boudin-specific thing.

NYC’s DA Cyrus Vance Jr. doesn’t seem to be notoriously soft on crime, but as I’m not really that up on NYC politics it’s possible this is just a case of another soft-on-crime DA discouraging arrests. But as much as I like the easy “Boudin told cops not to bring him criminals” narrative, the more data points we find showing a drop in shoplifting arrests circa 2020 the more we should be looking at non-DA related causes. (Note: I might update this with more data points from more cities later).

Other explanations that I really should look into but have run out of time for include stuff like “people are afraid to shoplift if they might die of COVID” and “People don’t need to shoplift if the government gives them cash payments several times a year”.

Do people really give up on reporting things?

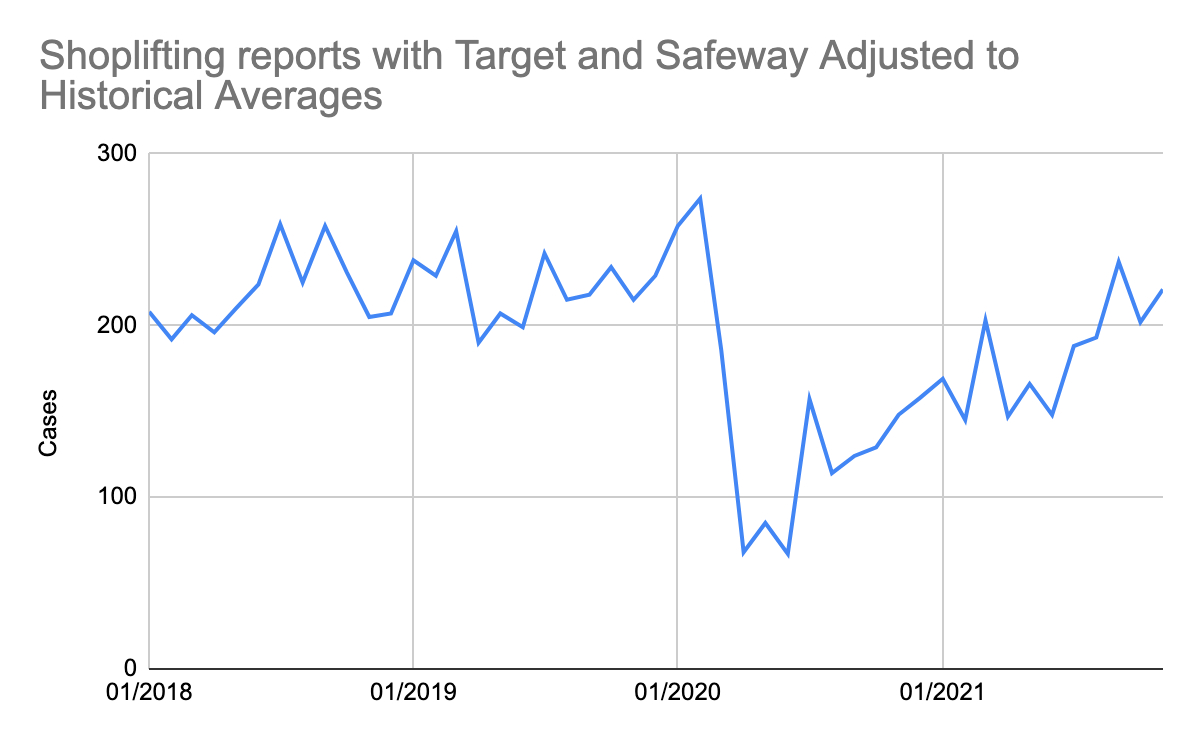

I think the strongest argument ADS makes against there being a real shoplifting epidemic in SF is this chart:

Adjusting for a couple huge spikes that have to do with reporting rates changing at a couple individual locations, this chart shows what appears to be a pretty normal reversion to mean. But it gets weird for me here, because it’s literally just a couple retail locations that either did or might have changed the way they report and started pushing 12000% of the reports they used to.

Previously, this location had reported just 1 incident per month, compared to 120 incidents in November.

The nice things about extreme changes in percentages like this is it tells us something. If the average Target is reporting <1% of its shoplifting we can pretty definitely say that the bottleneck isn’t “lack of shoplifters to report”, since nobody (or almost nobody) thinks shoplifting got 120 times worse. But then we have to ask why they weren’t reporting very many incidents before, and it gets wonky.

My unfounded but plausible assumption here is that the actual bottleneck is employee time; i.e. that the manager can only make so many calls to the police a day, regardless of how many incidents there are to report. That lines up with the story the Target in question tells here, which is that they changed their reporting system to something more efficient and suddenly were able to report more of what they were seeing.

If it’s the case that employee time available to report crimes is the big factor here (which is not definite!) then it also helps explain why shoplifting went down during COVID; you no longer need petty criminals to be personal-health types. You just need understaffed stores, which we know we had.

The flip side of that is that if it’s true we also have no idea how accurate ANY shoplifting counting is during the heavy-covid-restriction period; there could be one case at a particular store or 10000. The number you’d end up knowing only indicates how long Assistant Manager Teresa has between customer complaints to make police reports that she knows from experience usually don’t produce any results.

I think the text indicates this, but in case I was unclear: I don’t actually think any of the things ADS wants to believe (his conclusions, where he says the data leads) are necessarily wrong. Near as I can tell, he’s making or implying the following basic claims:

1. SF’s crime wave, if it exists, isn’t because of its $950 felony theft threshold.

2. SF’s crime wave, if it exists, isn’t because Chesa Boudin is soft on crime.

3. Judging by Walgreens stores alone, not a lot of stores have closed in SF.

4. Most people who think there’s a big shoplifting epidemic in SF are working from faulty information.

5. Chesa Boudin isn’t soft on crime.

If those are his claims, I can’t disprove most of them.

1-2: If SF has a shoplifting epidemic, it’s probably because of a lot of reasons, not just one in isolation. Actual shoplifting convictions are rare in the first place in SF; the most convictions in a single year since 2011 was 225 in 2015. Yes, nine is less than 225. No, I’m not confident that either number is enough to actually deter that much shoplifting, whether Boudin caused the problem or not.

3. This seems true in the narrow sense of “just Walgreens”, and I think that’s probably good enough here.

4. This was at least true of me; I mostly bought this without looking into it at all, just based on biases.

5. This one seems clearly wrong, unless we go so deep-semantics in an argument that we eventually conclude “not filing as many cases and dismissing, diverting or plea bargaining out the vast majority of them to minimize actual punishments” is a hard on crime practice.

Or we could say he’s not making claims, but just responding to them like I’m doing here. That’s fine too.

With that in mind, I’ve been asked during the edit process why it’s worth it to write the article at all. If I don’t disagree, and I can’t prove the hypothetical claimants ADS says are wrong are right, what’s the point?

I think that when I approach an argument like this, the things that seem most important to me are what people will end up believing if they accept the argument as true, and whether or not the argument justifies that belief. I tend to weight these about evenly (fun fact: depending on how long you think about it, you might find your opinion on which weighting is more inappropriate might switch back and forth a few times).

In this case, I think someone casually reading the article might come to believe the implications of it are true - i.e. that there’s no shoplifting problem at all, and that if there were it’s certainly not because of a failure of a particular left-aligned policy or a particular left-aligned district attorney. But note that the belief isn’t actually my problem here.

I’d care if I thought the hypothetical readers were believing an untrue thing, but I don’t know this to be that with any reasonable level of certainty. What’s left is the standards that determine what they come to believe, both in the sense of what they accept and what is offered to them.

While someone walking away believing that a supposed crisis is overblown isn’t a huge problem, the reasons they believe it matter. If a person can be convinced of a true thing with a bad argument of a certain quality level, they might be covinced of a false thing with the same argument.

Since ADS skipped over the “there are other possibilities” hedge straight to much stronger it’s-not-even-arguable-these-dumbasses-are-wrong levels of certainty, it would be easy to walk away from from the article with a stronger belief than is warranted from the evidence he presents. You shouldn’t. Hold out for his better stuff.

It happens I think ADS is generally pretty good, and I don’t think he’s wrong to push back on beliefs that are ill-founded - I’d be a hypocrite if I did. While that leaves me in the awkward position of critiquing a critique I don’t even necessarily disagree with in terms of conclusions, I think it’s worth it even if this one ends up being a little boring, It might end up encouraging better work where otherwise high standards might fall. I don’t think I’d like it in the moment, but I hope someone would do the same for me.

The first argument is totally specious. There is a huge difference between not a felony and decriminalization. In Oregon, stealing less than $100 is a not a felony. It is a Class 3 misdemeanor with penalties of up $1250 fine and 30 days in jail. Decriminalization means there is no penalty. There is no relationship between the two.

"a felony:

'(D) the value of the property stolen is less than $2,500 and the defendant has been previously convicted two or more times of any grade of theft;'

Whoops! Texas has a three strikes law. So while their floor is pretty high if they’ve been caught stealing bubblegum twice and convicted, that third pack of Bazooka Joe still costs pretty dearly."

Consider clarifying your paragraph. It looks to me like the floor is pretty high if they *haven't* been caught two or more time; when they have, then the monetary floor is ignored (because of the two priors).