I’m beginning to realize I care a little bit too much about truthfulness.

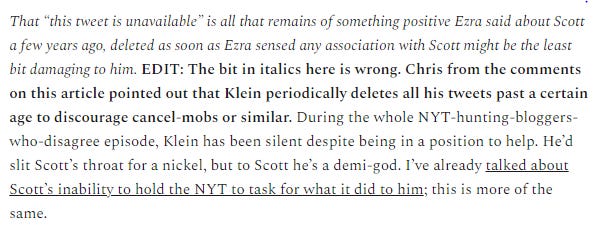

This isn’t humblebrag. I’m not especially great at being truthful compared to the average person who puts some level of effort into it. Like anyone else, it’s much easier for me to see and call out dishonesty from my perceived enemies than it is to acknowledge the same in my own bubble. I get called out occasionally for instances where I was moving too fast, assumed to much and was dishonest by means of not doing due diligence. You can see some evidence of that here:

I can’t stress enough that I’m not a superman of honesty. But I do care about it. When I make a mistake like the one above it’s embarrassing, because I know I did something wrong; I could make an excuse that this isn’t a lie, but I also know that even a small amount of extra effort might have prevented me from saying something factually false. My forehead burns in shame. I can edit and make corrections, but I know I’m that much less credible. More importantly, I know I’ve done something wrong; lying is bad, I shouldn’t do it, and a person reading my blog would be justified to consider it worse in a general way when they encounter this kind of untruth.

Because of all this I’m shocked when I run into viewpoints that seem to devalue truth. Part of this is just the typical mind fallacy at play - we all tend to assume that everyone else thinks like us and are shocked to find they don’t. Despite that I think there’s also a sea-change in play here; where once even people who had no regard for truth had to at least play along and pretend they did, I’ve recently been noticing more and more people being comfortable admitting that truth has little or no importance to them as an independent value. This troubles me, so I’m pulling some examples out to show what I mean; note that these examples aren’t of lies and I’m not accusing the subjects of the examples of lying within them. Instead, these are examples of concerning attitudes towards lies that I think represent a changing attitude among some “thought leaders” of note.

Matthew Yglesias recently wrote a post kind-of sort-of defending rationalists; you should go read it if nothing else to keep me accountable, since I’m splicing/compiling some of his quotes below to save space. Yglesias represents rationalists as a little silly and too concerned about things that don’t matter, but he also mostly thinks they shouldn’t be put down like sick dogs, which is a qualified point in his favor I can’t confidently attribute to every journalist. In the piece, he mentions that rationalists at least try to focus more than average on factual truth:

Rationalists’ big thing is that the natural human process of cognition is capable of reaching accurate results, but that’s not really the default mode. And rationalists are not just aware of this — they think it’s a big problem, and they try really hard to push back on it and develop better reasoning skills.

But of course, there’s more to it than predicting. The key to Metz’s point is that part of the practice of rationalism is that in order to do it effectively, you have to be willing to be impolite. Not necessarily 24 hours a day or anything, but when you’re in Rationalism Mode you can’t also “read the room.” A rationalist would say that human psychology is over-optimized for reading the room, and that to get at the truth you need to be willing to deliberately turn off the room-reading portion of your brain and just throw your idea out.

Matt is trying his best to obscure it here, but the term “reading the room” is increasingly becoming journalist speak for “not telling the truth for other reasons”, or, less charitably, “lying for your own gain for convenience”.

EDIT: The Resident Contrarian Proofreader Taskforce members are pushing back on the idea that “reading the room” means what I think it does here, and I think they are right that in general use it means something like “to use simple, polite tact”. But Matt isn’t talking about rationalists he’s running into at cocktail parties; he’s talking about the entire movement as a group. Even discounting the instances I’ve seen of “read the room” being used to mean “Shut up, bringing up this objection is wrong” in general discourse, when Matt brings this up in regards to the entire discourse of an entire movement, it’s hard to imagine an implementation of this norm that doesn’t involve factual objections just not being made when sacred cows are present.

Since “lying because you don’t like the implications of the truth” isn’t as snappy as “reading the room”, the latter phrase has been gaining popularity among his set as of late. He does get a little more granular on what he means:

But in progressive circles, it is common to observe the norm that because the struggle against racism and misogyny is important, it is impolite to dissent from an anti-racist claim or argument unless you have some overwhelmingly important reason for doing so.

So we get a little of what he means here - he believes these efforts to be inherently noble and important in such a way that they should be immune from pushback except in the face of the most imperative of need. He then senses his point is a little weak and creates a caricature of his opponents:

In the (liberal, coastal, urban, very political) circles that I travel, everyone (especially parents) knows and acknowledges that men and women are, on average, different in ways that end up mattering for the distribution of outcomes. But everyone also believes that sexism and misogyny are significant problems in the world, and that the people struggling against those problems are worthy of admiration and praise. So to leap into a conversation about sexism and misogyny yelling “WELL ACTUALLY GIOLLA AND KAJONIUS FIND THAT SEX DIFFERENCES IN PERSONALITY ARE LARGER IN COUNTRIES WITH MORE GENDER EQUALITY” would be considered a rude and undermining thing to do.

You see the tricks of phrasing here; Matt knows he’s weak in this argument so he paints a picture of an uninvited guest at a party accosting people in private conversations rather than people participating in normal discourse. But once we get past that, we kind of understand what he’s saying: we’ve already decided this issue is real, caused by bad people doing bad things for bad reasons, and correctable by punishing them. You bringing stupid studies that say we are wrong is very rude, and Matt is a bit offended that you’d be such a boor as to think that factual truth should have any bearing on his preferred reality.

After calling everyone with the temerity to think truth is important in the face things-his-friends-just-decided an autistic mansplaining sea lion, Yglesias does eventually get around to softening things just a little:

But I think that in the Trump era, journalism as a whole has tilted too far in Lowrey’s direction, with too much room-reading and groupthink and not enough appreciation of the value of annoying people with inconvenient observations.

But even with this, it’s clear Matt’s appreciation of truth is at best conditional; there are some instances where he finds it useful enough to include in the dialogue, but others where he believes all decent, good people should choose to ignore the truth and and make fun of those who can’t read the room enough to know which shared fantasies are important enough to protect from reality.

This is one version of the truth-is-not-important game, that some lies are preferable to some truths and thus outweigh them. Matt’s detractors (I’m one) generally argue that he does this all the time; his consistent position is something like “whatever the journalist branch of the left believes is the reality we should all accept”. In defense of this, he will often make brilliant observations about the world, only to ignore their implications if they touch on the possibility of making him change his mind about any of his favorite viewpoints. There are other versions of the diminishing importance of truth we can look at, however: Zeynep Tufekci provides the next good example of this.

In a recent featured piece at The Atlantic, Zeynep details a number of mistakes made in the pandemic response that she feels present learning opportunities for the future. Among them, she talks about the public health community’s fear of risk compensation, the idea that allowing average people to take logical steps towards their safety will result in the same people becoming reckless, offsetting the good those measures might have done:

One of the most important problems undermining the pandemic response has been the mistrust and paternalism that some public-health agencies and experts have exhibited toward the public. A key reason for this stance seems to be that some experts feared that people would respond to something that increased their safety—such as masks, rapid tests, or vaccines—by behaving recklessly. They worried that a heightened sense of safety would lead members of the public to take risks that would not just undermine any gains, but reverse them.

The theory that things that improve our safety might provide a false sense of security and lead to reckless behavior is attractive—it’s contrarian and clever, and fits the “here’s something surprising we smart folks thought about” mold that appeals to, well, people who think of themselves as smart. Unsurprisingly, such fears have greeted efforts to persuade the public to adopt almost every advance in safety, including seat belts, helmets, and condoms.

To understand what she’s talking about, we need to dig through her links a little; the first eventually leads to Fauci’s initial dishonesty when recommending people don’t wear masks:

In the clip, Dr Fauci says “There’s no reason to be walking around with a mask. When you’re in the middle of an outbreak, wearing a mask might make people feel a little bit better and it might even block a droplet, but it’s not providing the perfect protection that people think that it is. And, often, there are unintended consequences — people keep fiddling with the mask and they keep touching their face.”

And then eventually his motivation for the lie, which was not a sincere belief that masks were counterproductive:

At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, Fauci originally discouraged mask-wearing by the public because he was concerned about PPE availability for health-care workers. “We didn’t realize the extent of asymptotic spread…what happened as the weeks and months came by, two things became clear: one, that there wasn’t a shortage of masks, we had plenty of masks and coverings that you could put on that’s plain cloth…so that took care of that problem. Secondly, we fully realized that there are a lot of people who are asymptomatic who are spreading infection. So it became clear that we absolutely should be wearing masks consistently.”

So we have a situation where the public health community initially lied about masks, perhaps for what they thought were good reasons; this almost certainly lead to unnecessary deaths. But Zeynep does not seem to care about this; she does not mention the lie at all. Her only concern seems to be that the lies were not effective because the gamble that motivated the lies seems not to have panned out. Her conclusion on the lying-to-the-public issue:

But time and again, the numbers tell a different story: Even if safety improvements cause a few people to behave recklessly, the benefits overwhelm the ill effects. In any case, most people are already interested in staying safe from a dangerous pathogen. Further, even at the beginning of the pandemic, sociological theory predicted that wearing masks would be associated with increased adherence to other precautionary measures—people interested in staying safe are interested in staying safe—and empirical research quickly confirmed exactly that. Unfortunately, though, the theory of risk compensation—and its implicit assumptions—continue to haunt our approach, in part because there hasn’t been a reckoning with the initial missteps.

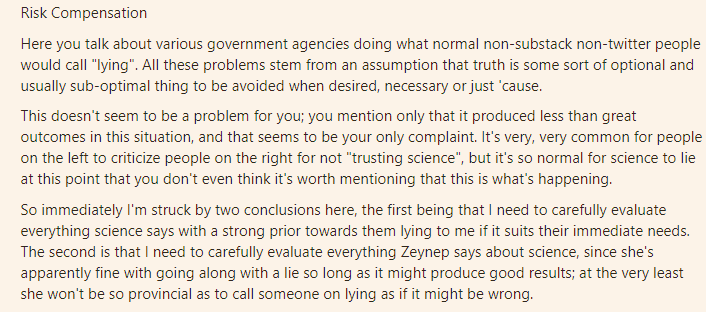

It’s hard to read this in such a way that doesn’t lead to the conclusion that Zeynep is A-OK with lying, so long as you think it might lead to an outcome you want; she seems to believe this even when faced with a situation where it likely killed tens of thousands of people. You might think this is a little harsh; so did I. Conveniently, Zeynep was running a discussion thread about the article here, giving me the opportunity to object:

Zeynep responded, sidestepping the issue of honesty to the extent she responded at all:

It’s nice to be charitable, even if I don’t do it very often. But it’s hard to do so here. Even when it’s pointed out to her, she just doesn’t seem concerned with the truth; lying, it seems, is just something you do when you think it’s necessary to get something you want. When it’s pointed out to her that she might be concerned about the lie itself, the pushback isn’t that it wasn’t a lie, but instead that the real problem is that the motivation for the lie was, in hindsight, flawed.

To be fair here, I’m reading a lot into what Zeynep’s omits; I’m pointing out things that didn’t make the cut. But even in the best case, she’s in a particular mental positioning where something like an outright lie told to millions of people doesn’t stand out as an obvious pandemic mistake or concern, even where it’s likely to have caused a significant amount of avoidable death.

It’s telling that she mentions trust issues when addressing other arguments I made - an increasing amount of people don’t trust officially recognized experts on matters of science. This shouldn’t be surprising when even sources considered to be generally reliable like Zeynep consider lying to common people a matter of course. But this kind of lie is so common that people in Zeynep’s tier seem to have lost the thread; they seem confused why they shouldn’t be considered trustworthy while at the same time considering a willingness to lie to be a beneficial norm.

In terms of defensibility, Zeynep’s and Matt’s positions regarding truth both have an advantage the other doesn’t. Matt seems to believe truth is valuable while not being a terminal value; for him, it’s good to be truthful so long as it doesn’t get in the way of something else you want. Zeynep’s disregard of truth at least nods at utilitarianism; she doesn’t seem to notice a difference between truth and lies at all, but she at least believes she’s working towards a goal we all agree is noble, one of reduced death in the face of a pandemic.

Those positions give you an idea of the way each probably models the world. Matt believes there’s a perfect direction for progress to pursue; he is pretty sure he knows who the victims are and who the villains are. In this model, acknowledging the damage a truth does to a position the good guys hold is actively assisting the bad guys. The implications of Zeynep’s position are more limited; she thinks that things like the pandemic are bad enough that certain actions are required for a good outcome, even if they are things like lying, misleading and withholding information. It’s important to note that ignoring the truth in those models makes a lot of sense so long as the right move can be definitely known. We know at this point that the lies the public health community told were counterproductive because the right choice wasn’t definite, and we can at least suspect that Matthew Yglesias does not possess sole ownership of the truths of society, culture and politics. Given that uncertainty, the truth-dismissing nuance they hope to grasp is difficult in a way that might lend truth the utilitarian edge, even before considering morality.

I want to emphasize again that I’m not accusing either of these people of lying here; their use in this article is purely to emphasize attitudes towards truth that I find concerning. To go a little further, I selected each of these people because they generally bring something valuable to the table. Zeynep has been right about various things related to pandemic response other people missed and invites critical feedback of her work. Yglesias often produces real and interesting insights on subjects he tackles, even if he has always kept the implications of those insights at arm’s length, refusing to let them come near his cherished core beliefs.

But because both of these authors are valuable - because they represent different branches of the worth-listening-to tree - they also represent a cohort of people you would wish had a more-than-casual regard for truth. You would hope people who wield the level of respect they do would themselves have a similarly intense respect for relaying accurate, honest information even when it seemed to them to be inconvenient or even counterproductive from an elite point of view. But neither do; both have moved to a post-truth-as-terminal-value world.

As I said at the opening of the article, I understand that not everyone believes the same things about truth that I do. I also can’t lay any claim to being perfect on this. But if I grind on the issue a little, it’s because I think it’s important; I think we are trading any trust or credibility voices like these used to have for immediate political or utilitarian advantage, acting as if that trust and credibility will never run out. But we can already see that the confidence being traded on is finite. People already explicitly don’t trust any news source that doesn’t cater to to their particular spot on the political spectrum; most also understand that the sources that do cater to them aren’t consistently truthful, even if confirmation bias leads them to never bring it up. I’m as guilty of the last as anyone, for the record.

It’s an unrealistic ask, but if I could convince anyone to take action based on this article I would hope they’d push for honesty from their own side; if I’m that for you, please call me on inaccuracies or places you don’t think I’m playing entirely above the board. I’ll do my best to adjust. Since a publication on the left isn’t likely to care about a complaint from a non-customer in the right-leaning side of the political spectrum (and because the same is true if the alignment of the complainer and the publication are flipped), any movement back towards vigorous honesty norms likely has to start with each of us criticizing our own.

I have a very limited reach compared to the big boys; I know this, and I don’t expect that this article will have any huge effect on this problem by itself. But as pithy as it may sound, any movement towards anything good has to start somewhere. People have always lied, but until recently we could count on a general agreement that this was wrong. I can only hope that whatever limited influence I wield moves things in the right direction. I honestly, truly hope it does.

So, do you think you care too much about the truth or not? You say so in your first sentence, but the rest of your article seems to indicate that you actually think you care the right amount about the truth and the rest of the world is wrong.

In your construction, Yglesias is basically saying that rationalists value truth over tact, no? I certainly value truth over tact, but I bet Yglesias would actually argue that the two needn't be in opposition for "normal" people. I think that's wrong--a dedication to the truth absolutely means we need to dismiss tact, but it's not an unusual argument to make. And I'm not at all sure that making that argument means you have a lower standard of truthiness, but maybe?

I think Zeynep doesn't get what you're after at all. I'd actually be interested in her response here. I think her response is just that the lies were immaterial to the point she was making, even though it's your central point--why didn't she address the lies? The Fauci lies are, to me, the most problematic thing about him, but is his job actually to tell the truth? Suppose for a minute that he's actually able to save lives by lying (it's not hard to imagine a world where that's the case), is his lying justified? Note that I do not think that's the actual case here--I think his lying has cost lives, but in the hypothetical situation, should he lie?

Thanks man.

I've been working more aggressively recently to put filters on my reading habits to minimize exposure to writers who don't put a high priority on factual truth. I really appreciate this post.