Kinda-Contra Erik Hoel on The Implications of Massive Fraud

Cutting EAs Some Slack, and Marginal Moral Activity

(For legal reasons, every time I say anyone did anything in this article, I mean that it’s alleged that they did it. The evidence here seems to be about as strong as evidence can be, but I’m not a court.)

There’s a limited timeframe for writing an article on a topical subject, or at least there’s supposed to be. The general idea is that you want to get something out as quickly as you are able while still maintaining quality. If you get lucky, you might get to be one of the official articles people use to explain the issue to other people on Twitter, and thus get a zillion views, money, fame, and a big bump to your household-name levels.

I’m way past that timeline as relates to the whole Sam Bankman-Fried (SBF, so I don’t have to keep typing it out) fraud story. I got a little too into the holidays, sorry.

After my last podcast appearance, the feedback from some friends was that it was very nice, but they were also normal people with lives and didn’t necessarily know what I was talking about at all points. I’m taking that to heart; some of you probably don’t know much about this story. In that spirit, here are some bullet points:

Sam Bankman-Fried is/was a very rich guy who made his money by running a crypto exchange, which is kind of a platform where you can park your crypto and have it be used in various hard-to-explain investments to grow your principal.

SBF was at the very least expected not to take funds from that exchange and use them in a bunch of tricky/risky ways to prop up other businesses he owned or had close connections to. He did this anyway, and people noticed.

Once people noticed, there was a run on the bank itself - people withdrew their funds as quickly as possible. Many people lost some or all of their investments. The value of Crypto tanked. Everything went to shit in big, confusing ways which nonetheless hurt a lot of real people in a very real way.

This was all very crazy, but it was even more significant for a lot of my audience because of SBF’s involvement in the Effective Altruist movement. SBF was a major millions-and-millions of dollars funder of various EA causes, and was/is inextricably linked to the movement for most people in the know about both entities.

A lot of people don’t like the EAs for a lot of reasons, and as such this whole debacle represented an opportunity to count coup; for a lot of folks, it was proof of all their worst fears and validation of all their EA-induced willies.

I’m on record as having a sort of instinctual revulsion of the EA movement, so all this should be red meat for me. When people assert that EAs should feel bad about this, I should probably just feel great as a result and let it ride. I even did that for a while, but recently I’ve thought better of it; I think the EAs are probably getting somewhat rougher treatment here than they deserve.

With great frustration on my part, here’s a partial defense of the EA in the matter of the SBF debacle.

The Hoel-esque Take

Erik Hoel does a pretty good job writing what I feel is the winner of the well-explained, EAs-caused-this-and-should-feel-very-bad-indeed takes to come out of the SBF mess. I’m broadly responding to what I believe to be an amalgamation of the argument he makes there and others like it that I’ve heard - that EA philosophy made something like SBF inevitable, that it was destined to happen, and wholly attributable to EA in the sense that they are responsible for it.

I’m repeating that you should absolutely read his article, but I perceive Hoel’s and others’ arguments to revolve around a few specific ideas:

SBF genuinely subscribed to an act-utilitarian philosophy that is not uncommon or controversial in EA circles.

EA philosophy encouraged risk-taking in a way that caused and could have been expected to cause SBF to be irresponsible in the way he seems to have been.

The overall scope of EA involvement with SBF makes them partially or wholly responsible for SBF; he’s a product of their environment, and exists as a result of things they think and do.

Note that I’m responding to an amalgam here; not all the views in the article are Hoel’s and shouldn’t be taken as such.

On Taking Money

To my eye, the strongest/most strident form of EA/SBF criticism is that the EAs shouldn’t have taken his money at all and in doing so irreparably tainted the movement.

I sort of daydream about getting blog funding. The way these particular fantasies work is that someone (anyone, really) comes in and says something like this:

Hey, RC! I’ve just read through your entire archive, and I liked it a lot. I think you are doing some real good, and I’d like to fund that so you can write more. Here’s an amount of money that replaces your day-job income! Go and write! Take more naps!

I know it’s not incredibly likely that this will happen but I think about it a lot, to the point where there are variations on the theme; sometimes I win the lottery, while other times about 2500% more people voluntarily pay for the blog than do right now. But at no point in the fantasy do I ever say “Hey, wait - could you please prove in some firm way that you are a good guy who is not currently doing felonies?”

And it’s not just that I’m acknowledging here that I like money and that I’m lazy (both of these things are true); it’s that I’m not sure that anybody should be doing this, or that they could if they wanted to without crippling the ability of charities to raise funds in general. There’s no reliable, easy way to confirm that someone is a great guy who is never, ever going to do anything bad.

Any process I can think of that EAs might have pursued ends up looking something like this:

SBF shows up and offers you $2m to support your efforts to convert mosquitos into clean drinking water in Nicaragua.

You ask “Hey, are you a good guy who doesn’t do horrible felonies?”. He says he isn’t, that he’s a nice guy who gives to charity.

You do some Googling and find he’s some sort of Crypto guy who isn’t thought to be a mob boss or anything, and that he’s given a bunch of people money in a way that generally seems to be normal, if in greater numbers than usual.

You do some further Googling and find out there’s no way to tell if any particular crypto thing is a scam, but he runs an exchange that seems legitimate.

You… contact the FBI? The FBI says they don’t talk about that kind of stuff and that it’s weird that you are calling them.

If you were a charity in this situation, you’d find that SBF didn’t have any current, confirmable felonies on the table to find. He wanted to give money for you to do work you thought was important, and not taking it would mean you would do less of that work. Anything more intense than this (say, asking to see the entirety of a giver’s financial records) would run a high chance of scaring them off, if you hadn’t already.

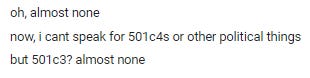

Against all odds, I have a friend who has worked at a high level for series of named charities you’ve heard of. I poked him to get some context for this, basically asking what the normative responsibilities of non-political charities are in verifying the moral fiber of their benefactors. He said this:

And that follows; there’s just no way to meaningfully vet most givers that still allows you to take in money efficiently - the level of scrutiny EAs would have had to apply to SBF is both unscalable and would set up a hurdle between givers and giving that most would fail to get over.

So while I might want to morally indict the EAs over this, it’s not clear how I can in a justified way. I can sort of cobble together something like this:

See, this is different because he gave so much money, and to so many different parties. There should be a bigger burden there.

But that’s post-hoc reasoning (since that norm doesn’t seem to exist otherwise) and is made worse by the fact that most due-diligence processes probably wouldn’t have caught SBF anyway. Right up until one of his competitors spent a bunch of time examining his balance sheets, nobody knew this was going on; the subset of things that would have made accepting his money “safe” seems to be entirely composed of things that would keep people from accepting charitable funds at all, and nobody wants that.

On Being Buddy-Buddy With The Devil

The next accusation I’ve heard goes something like this:

Yeah, I mean, maybe you take the money. But EA went a step beyond that; they lionized the guy. They did interviews with him and held him up as an example of what everyone should be doing. He was a wolf in sheep’s clothing, and they fell for it.

This is a bit subjective in the sense that it’s hard to know what is or isn’t over-enthusiastic, but let’s take it at face value for now. For the sake of argument, let’s pretend you could find an article that indicts EA people perfectly here - say it’s written by The President of All EA People. Let’s say that the article held SBF up as a Jesus-type figure of exceptionally generous giving; here, the article says, was someone who is doing it right - he was making a ton of money with the goal of being charitable, then following through by actually giving it away.

I think most would intuitively agree that it would be reasonable for the author of that article to feel embarrassed in hindsight, but should he feel like he transgressed a moral rule? Which one? These are utilitarians; “hold up the shining example to drive more funding to create better outcomes” is completely in line with their moral system.

Even if they were deontologists, I can’t think of any system that has a rule that reads “If someone wants to donate money to your cause, you can take it but you should be very careful in terms of lauding them for doing so, having near-100% confidence they are deep down a good guy who won’t, in the future, turn out to be terrible in a way nobody had evidence would happen”.

Mostly this seems like something most charities might do - when someone gives them a bunch of money, they give them credit for it to create an incentive for others to follow suit. There might be something I’m missing here, but this seems like another place I can’t fully crucify the EAs; there’s just not enough tree to support the nails.

On Marginal Moral Activity

Pretend that from birth you’ve been a member of Moral System X, which you think is superior to all other moral systems. When you were young, it seemed clear that every other moral system would fail when tried, that the foundations of other moral systems were so clearly wrong that they’d inevitably fail to compel meaningful moral behavior.

One day that all changed. You got out into the real world a bit and met a bunch of different kinds of people, and eventually you ran into someone from another moral system whose behavior was in all ways superior to yours. They were kinder; they treated people better and thought of them more generously. They were more active; they took time to proactively pursue good.

At the same time, people started pointing out the bad players in your moral system - the conmen, cheats, and liars that every moral system ends up with (hell, even Gandhi was some kind of weird sex pervert). You then probably pointed out that their system had bad players as well, and eventually came to the conclusion that there’s some variance in how moral/good/nice people are that is just inherent to their character in a way that operates independently from the moral system they subscribe to.

Coming back to reality, I think most people would look at SBF and conclude that he was naturally inclined to risk-taking and flights of ego that would tend to drive him to bad behavior of the kind he was eventually caught doing. In other words, he was born as a three on the 1-10 moral scale; it’s far from sure, but it’s imaginable that given no other inputs, he’d probably naturally be a pretty bad guy.

In the Hoel article I linked above, Hoel asks this question:

The question is not: did anyone in EA (outside of the EA members of FTX) know about its shady dealings? The question is: was the FTX implosion a consequence of the moral philosophy of EA brought to its logical conclusion? This latter question is why some people are trying to create as much distance between SBF and EA as possible.

I disagree with that framing a bit. Hoel is asking whether or not EA-type morality drove SBF inevitably towards this behavior, but I think that probably makes an assumption about morality that isn’t exactly true - that subscription to a moral system has an unlimited influence on one’s behavior. Simple observation of the world shows that this isn’t so, and it’s clearly visible in Christians who act in opposition to scriptural law or utilitarians who routinely create disutility.

I think a better framing is one of marginal moral activity, which I’m defining as the distance a person moves towards “good person” or “bad person” on an imagined sliding scale as a direct effect of their moral system. Viewed through that prism, the relevant question isn’t “Is EA philosophy entirely responsible for SBF’s sins?” but instead something like this:

Did EA philosophy cause SBF to commit fraud where he otherwise wouldn’t have done so? If so, why did it compel him to do that, and how much work did it do above and beyond his normal personality to achieve the bad result?

If he would have always done the bad thing with or without EA, why wasn’t EA philosophy sufficient to stop him? What would it have had to have been to have an effect here?

Hoel’s conclusion is something like “Utilitarianism says that there are no hard and fast rules, so long as what you are doing is likely to create good outcomes. It would have been really easy for SBF to convince himself that an effectively unlimited amount of risky behavior was justifiable here.”. As Hoel notes, SBF wasn’t all that shy about this, and it wasn’t that inconsistent with the sort of high-theoretical musings of EA people:

Also within the mainstream was SBF’s idea of maximizing the expected value of his giving via risky business ventures. Here’s him with EA leader Rob Wiblin from 80,000 Hours:

Sam Bankman-Fried: . . . Even if we [FTX] were probably going to fail, in expectation, I think it was actually still quite good.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah.

Or, in plenty of cases, it was the EA leaders who laid out reasoning about risk taking, and SBF was the one nodding.

Rob Wiblin: But when it comes to doing good. . . you kind of want to just be risk neutral. As an individual, to make a bet where it’s like, “I’m going to gamble my $10 billion and either get $20 billion or $0, with equal probability” would be madness. But from an altruistic point of view, it’s not so crazy. Maybe that’s an even bet, but you should be much more open to making radical gambles like that.

Sam Bankman-Fried: Completely agree.

In conclusion: none of SBF’s beliefs seem particularly unusual by EA standards, except that he took these principles to such literal extremes in his own life.

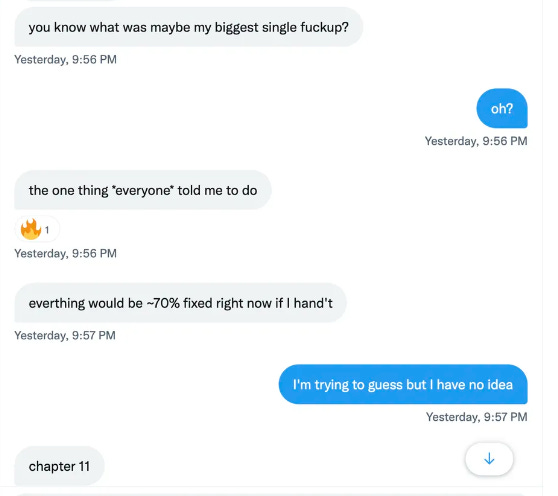

When your moral system is “there is no bad except bad outcomes”, the only thing that would have kept SBF on the straight-and-narrow would be if he thought he was capable of failure. But every indication is that this isn’t a thought he’s capable of thinking:

Behold the absolute confidence; this isn’t a man who does well with “do whatever you want, so long as you are confident about it” moral systems. Where Hoel and I agree, it’s that utilitarian-type morality doesn’t do much to stop this kind of ego-monster.

But even while I’m arguing that there’s nothing in EA morality we’d expect to stop SBF in this scenario - that it didn’t inspire marginal moral activity to keep him from badness - I’m still reluctant to say they created him whole cloth in the way that Hoel seems confident they did.

Some things really are built-from-scratch monsters, as Hoel says. But as Gessler notes, some boots are just bad from birth.

Again, I’d much rather be scorched-earth-destroying my cultural outgroup right now. If you’ve ever done that, you know it’s fun - you get to feel a lot better about yourself without actually doing much work to make it happen. It’s the same reason I watch COPS.

But when I go to do that, I have to think about whether or not I would have caught this. And, frankly, much smarter-in-that-way people than me were watching FTX/SBF and didn’t catch it. I don’t just mean EA people; the Feds didn’t catch it, either. Anti-EA people didn’t catch it. Hell, at some point EA groups were pushing tens of thousands of dollars into prize money for (they claimed) essays criticizing them, and I don’t think any of them were titled “How SBF is clearly a criminal type and this will obviously blow up in your faces”.

I have to think about whether or not my own moral system is 100% effective at stopping frauds from gaining a foothold, and it just isn’t; there’s Joel Osteens everywhere you look, being weird and scummy and doing weird scummy things. It turns out “I am Christian/Utilitarian/Hindu” isn’t that great of a statement when it comes to guaranteeing that someone is actually committed to good outcomes when it costs them something, and wolves still have no trouble finding sheep’s clothing.

Hoel’s take - again, not one I entirely disagree with - seems to be that EA philosophy was uniquely suited to create an SBF, and that this is a dagger that has already been sheathed in the heart of the movement:

Perhaps inevitably, a young college-age elite with a lot of potential and connections came along, and he ended up coming to the logical conclusion that EA should be taken as seriously as possible, and this, mixed with hubris borrowed from Wall Street and risk borrowed from crypto, was likely the Aristotelian formal cause of FTX’s collapse.

That’s why I think EA never recovers. Oh, many EA charities might be active in ten years, I don’t doubt. I certainly hope so, as in their outputs they often do a lot of good. But the intellectual and cultural momentum of EA will be forever sapped, and EA will likely dilute away into merely a set of successful institutions, some of whom barely mention their origins.

And yes, this is an indicator that we-do-what-lord-math-commands morality that assumes a humanity skilled at egoless, selfless activity often leads down monstrous roads; it’s a system that is just waiting for an SBF to judge that utility is best served by taking huge, unauthorized risks with other people’s money to enrich his pocket and pride to trigger a disaster.

And yet: Most utilitarians wouldn’t actually do what SBF did, I think. And at least some deontologists would. Yes, EA did not dissuade him, but that’s no guarantee that deontology could have. Created and uncorrected are not the same, and neither is proved here. Without that proof, it’s unclear that one man’s behavior can indicate the total failure of a movement; if one man’s behavior could, I’m not sure any movement would survive.

What I think is sure, however, is that what comes next is all-important. The effective altruists have been given a bloody nose here from a fist made out of indicators that a change of course is needed. They have a pretty good sign that spreadsheet morality, unchecked, causes plenty of unexpected disasters as the inputs curve toward infinity.

They at least kind of know the failure-mode of “anything is OK, so long as you guess it will turn out well”.

Presumably, a big part of keeping that “effective” letter E in the EA title is being able to adjust as new information comes available - being able to think hard about the kind of marginal morality their chosen moral system does or doesn’t inspire. It will be interesting to see if they do.

Something I've noticed from EA/Rat circles is a revisit of "tradition" as a valid input into their thinking. I believe that SBF's biggest problem was assuming he already knew everything he needed to know in order to run a multi-billion dollar business. Looking at the particulars coming out after the collapse, it's clear that neither he nor anyone at FTX even had a basic understanding of how to run any kind of business, let alone a multi-billion dollar one. They didn't have a list of employees. Like, no one knew or could have readily found out how many people worked there, what they were paid, what they did at the organization, or whether they were paying their employment taxes properly. That's the kind of stuff that small business owners figure out about the time they hire their first employee. It's basic and obvious to any mid-sized and above company (meaning a few hundred employees, which FTX had, or a few million dollars in revenue/expenses). But SBF thought he knew everything he needed, so that got overlooked and nobody cared. They also apparently didn't keep a list of their bank accounts, used QuickBooks for accounting, had few to no safeguards on money being spent (like, lots of people could just spend company money on whatever they wanted) and spent lavishly on perks for their employees (including themselves, family members, and friends - all of whom may or may not have been employees as well). All really stupid things for any company to be doing, and often illegal in like a dozen different ways. The whole crew was laughably incompetent, and the non-EA/Rat employees were apparently screaming about it, despite only having small glimpses of the core rot.

So back to my point about tradition. There's something to be said for doing things similarly to how they've been done in the past, even if you don't know exactly why. EA/Rat have previously all been about thinking it through and only doing what makes sense - i.e. cutting out all the stupid crusty and unnecessary junk that builds up around an organization. It turns out that those things exist for reasons, sometimes really good reasons. It's nice to see Scott Alexander and some others take a look at tradition and try to incorporate more to their philosophy. I'm not sure EAs can make that transition, and if they do I'm not sure they will still exist as some kind of new or novel idea or just become a fairly standard set of charity organizations with a tech-oriented clientele.

More to the point of your article, I think EAs have a philosophy that makes them extremely likely (in a way that other types of organizations really aren't) to fall victim to missing important information in their decision-making. They actively reject thousands of years of collective experience on the assumption that a very smart person can figure out everything they really need by the time they are in their mid 20s, and surpass everyone else who use that collective knowledge. They also do this while bundled with a philosophy that says to take outsized risks when the expected payout is larger than the expected risk. I think you can see where I'm going with this. They don't know what the actual risks are, and likely not the rewards either! Then they overwrite their ignorance with a philosophy that absolutely requires that they understand what the risks are in order to make a reasoned judgement about whether the risk is worth it. SBF (by that I mean him as a stand-in for huge gains using Rat philosophy) could not have have existed at Goldman Sachs, because they would have judged him too risk-prone and either sharply limited his access or fired him. They would have been correct to do this, and they would have absolutely been sure to do this, because they had the knowledge and experience to judge these things much better than SBF.

Current, existing EA philosophy really is in many ways specifically to blame here. They empowered SBF's idiocy and disempowered any checks and balances. Those things are core to the philosophy, as it currently exists.

Thanks for writing this. It's good and made me think:

1) What would you advise EAs do as a result?

2) What do you think is the moral responsibility of the median EA

3) If SBF was a 3 on some moral scale but EA made him a 2.5 that's bad right?

4) I do think the worst thing about SBF was that he was bad at math. This wasn't some galaxy brain deal with infinite upsite. It seems he was always gonna lose.