New Years Weight Loss Edition Part 1: All The Stuff You Never Knew We Didn't Know About Leptin

Imagine a potential future: You’re at a new years party, and as tradition demands you’ve been asked about your new years resolutions. You list a dozen things you’d like to do - build a ship in a bottle, see more of your native land, that sort of thing - and, almost as an afterthought, mention that you’d like to lose a few pounds. This last, it turns out, was a mistake of the highest order.

Your most annoying friend turns out to have read an article this year, and that article was about how weight loss is impossible. Fueled by alcohol and dimly remembered Redbook, they inform you that your resolution shed weight is impossible; your hormones won’t allow it. Just as soon as you lose weight your entire endocrine system rises up against the tyranny of your caloric austerity, forcing you to eat more and exercise less until your weight returns to its previous grandeur.

Convinced, you resign yourself to a future of coffeecake and ever-tightening waistbands. But must it be so?

The hormone your friend is dimly recalling is probably leptin, a hormone secreted by your fat cells. The general scientific narrative is that leptin acts a bit like an elastic band staked to your current weight; if you become heavier, excess leptin suppresses your appetite and raises your energy output until you drop the extra bulk. Conversely (and more relevantly), the popular story states that if you attempt to lose weight, you can do so only temporarily - your leptin levels drop with your body fat percentage, driving you mad with hunger and subduing your body’s metabolism to near-hibernation levels.

Of the two stories, the former is by far the more hopeful sounding - if it were true, the overweight could dose ourselves with leptin until such time as we just didn’t feel like eating and watch the extra weight effortlessly slip away. In this way, it would be a lot like the success story that melatonin has been for many - a natural hormone that, supplemented in the correct dose, would adjust for problems caused by modern food availability in the way that melatonin adjusted for issues caused by the electric light.

Unfortunately, there’s no evidence that leptin works this way. This study is one of the few I can find that actually tests to see if leptin causes weight loss, and the results are pretty unexciting. Lean participants show no effect at any point, while obese participants saw no effect at four weeks and only a mild effect at 20.

Weight loss science is predictably weird about this; it’s not at all hard to find claims that leptin works against weight gain, despite the near complete lack of evidence. And it took forever for anybody to notice this - leptin was first isolated in 1995, and it took something like 22 years for anybody to seriously question the idea that the effect it has on weight loss might not be symmetrical.

This weirdness gets weirder when you start to look into the concept of leptin insensitivity. The idea here is that since obese people have higher levels of leptin (about eight times as high) and yet manage to not lose or even gain weight, their bodies must be uniquely resistant to the hormone’s intended messaging. But there’s no evidence for this besides what I just said. Once you factor out the fact that sometimes high leptin levels don’t result in weight loss, there’s no reason to think leptin insensitivity even exists and you get studies producing quotes like this:

There are currently no methods for effectively assessing leptin sensitivity in a clinical setting. Such sensitivity is reportedly related directly to obesity in general and adipose-tissue volume in particular. A typical obese patient can be characterized by increased leptin levels and excessive OB expression in adipose tissue.64,65 Therefore, many studies consider hyperleptinemia as a key marker of leptin resistance,66–68 and previous associations between abdominal obesity and leptin concentration have been identified as and explained by leptin resistance.69 However, no clear criteria have been established for the diagnosis of leptin resistance.

So science decided, sans evidence, that leptin discouraged weight gain, then found that people with high leptin levels still gained weight and maintained it. They then tested just enough to find out they couldn’t induce significant weight loss by supplementing the hormone. Instead of then admitting they might have been wrong, they instead made up a disorder whole-cloth to explain away their weird attachment to an obviously wrong idea. It’s a bit like dark matter in that it creates a theory that something exists to explain an observed reality, but we accept dark matter mainly because better explanations generally have failed to materialize. In this case, you would think science might consider the possibility that some people eat for reasons besides hunger, but they absolutely refuse to do so.

As inexplicable as this might seem, it becomes a little bit easier to understand once you process the idea socially rather than scientifically. A scientist claiming that leptin resistance exists is essentially saying that anybody thin is only thin because their leptin is working and otherwise would be obese. The leptin resistant patient is then very clearly not to be made to feel responsible for their weight - there’s nothing they can do. To a kind person or a person who wanted to seem kind, this is an appealing rationale.

But whether it’s kind or not it’s apparent that there’s no strong evidence that leptin controls weight gain in humans, and we shouldn’t be waiting with bated breath for leptin-derived appetite suppressants to save us from holiday weight gain.

If leptin doesn’t discourage weight gain, then it becomes particularly interesting whether it prevents weight loss. As stated above there’s an idea that when a person loses weight and starts underproducing leptin as compared to their heavier self, their body reacts in a number of ways. The usual claims look something like this:

Weight loss causes leptin deficiency, which in turn causes food-seeking behaviors and overeating by removing one of the mental checks against over-feeding.

Leptin deficiency caused by weight loss induces a state of reduced energy usage, which encourages weight gain by “saving” energy to replenish fat stores.

There is no great evidence for the first proposition besides the fact that people who have lost weight often regain it. This at least isn’t necessarily science’s fault; it’s not easy to quantify how hungry someone feels, or how much and how intensely they think about food. When they do try to quantify this, however, hilarity ensues.

In this study, the authors sought to prove that leptin deficiency made people react more intensely to food. The researchers did a baseline fMRI of obese participants before the study while having them look at pictures of food and noted those results, then performed the same scan after participants had lost >10% of their body weight, and found that the second scan was lit up like a Christmas tree - clearly the participants were leptin deficient, and this was distorting their relationship with food.

This all makes sense until you take a second and realize what’s happening here - the first baseline scan was made of obese people while they were in a completely normal condition: Eating their own food and living their lives as normal, presumably reasonably sated. At the time of the second scan, the participants had been sequestered on a calorie-restricted all-liquid diet for weeks. The authors never once consider the idea that the participants might simply have a hankering for food not in the form of chalky, chocolate flavored nutrient shakes; it goes unmentioned, as if we’d expect no difference in reactions to a steak from a well-fed man as compared to a prisoner living on stale bread.

The one interesting question raised despite all this is whether or not administering leptin in this supposedly leptin derived state relieves these symptoms, and the study finds it does; after administering leptin to the patients, there are noticeable differences on the scans. It’s still an fMRI study and basically suspect, but discounting my bias against fMRI we are seeing our first evidence that leptin might matter in the slightest to a dieter. If this leptin deficiency is a long-lasting effect, it might actually be pretty difficult to keep weight off.

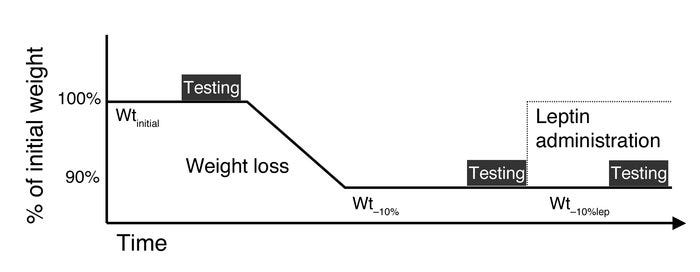

A second study from the same lead author gives us a little more to work with on timeline, and also addresses our second question: Does leptin deficiency cause metabolic slowdown that ensures weight lost is quickly regained? A similar study protocol was in place here: They tested leptin levels and energy use in obese people at baseline, after losing weight, and after maintaining lost weight but receiving supplemental leptin:

Energy expenditure. At all study periods, the respiratory quotient (RQ) at rest was not significantly different from the diet formula quotient (by bomb calorimetry) of 0.85. At Wt–10%, 24-hour energy expenditure (TEE) and nonresting energy expenditure (NREE; energy expended in physical activity above resting) were decreased out of proportion to changes in body composition from Wtinitial. The relationships among TEE, NREE, and body composition were restored at Wt–10%lep to levels present at Wtinitial (Figure 4). No significant effects of weight loss or leptin administration on resting energy expenditure (REE) or the thermic effect of feeding (TEF) beyond those predicted by changes in body composition were noted.

This looks like an actual change! Resting metabolism didn’t change, but energy used while exercising did! We have something solid-seeming, and it took me so long to find that it now almost pains me to bring up the timeline. Despite having 24-7 access to their research subjects, the researchers here chose to time their non-baseline tests to “immediately after the diet” and “five weeks after the diet”, respectively:

Following weight loss, daily caloric ingestion of the liquid formula diet was adjusted until weight was stable (designated as “Wt–10%”), and the same testing performed at Wtinitial was repeated. Subjects required an average of 7 weeks to complete studies at Wt–10% (range 6–8 weeks). Following completion of studies at Wt–10%, and while remaining on the same daily caloric intake, subjects received 5 weeks of twice-daily leptin injections in doses calculated to maintain circulating leptin concentrations at levels present prior to weight loss (designated as “Wt–10%lep”) and within dosing ranges that have been reported to have little if any effect on the parameters measured in this study in subjects at usual weight (25, 26).

We now have a question: Did the leptin do the work here, or did the study subjects just eventually recover from system-shock caused by an 800 k/cal Ensure crash diet? This matters for the previous food-picture fMRI study as well - if the same author used the same timeline, it’s hard to know if leptin supplements helped or just came along for the ride as people’s bodies naturally recovered from a huge, sudden weight loss.

Science isn’t a lot of help in making a judgement here - there’s significant disagreement on how long downward metabolic adaptations of this kind last, if they occur at all. To get an idea of the level conflict at play here of see this entire article, but particularly footnotes 4-16, if you have spare day to read them.

In the end here we are left with very weak evidence that leptin helps control weight gain and similarly weak evidence that such a thing as leptin resistance exists. We have slightly stronger but still very shaky evidence that leptin makes weight loss hard to maintain in the long term - either leptin or some other factor seem to reduce the metabolism after a diet, but the evidence is conflicting on how much or for how long.

This is another long article pointing out that evidence that pop-health articles take to be absolutely ironclad is surprisingly weak, but I spent a long time on this (and will spend a long time on the exciting conclusion in part 2) because I think this matters. Telling people that dieting doesn’t and can’t work in the long-term is great if you have a solution that makes it work. It’s even OK if it just doesn’t work and there’s no solution - at least you save people some time and guilt.

But if dieting can work - if these leptin-restrictions aren’t all-powerful - then shaky overstatements in the discussion pages of studies like this might convince some people not to even try. And not trying is a horrific thing in this case.

When I was younger, I was obese; not extremely so, but well within the lower bounds of the condition. At the time, everyone foolishly thought weight loss was possible, and I was young enough to believe them and give it a go. People thought weight loss could be maintained, so I tried that as well. I’m older now and overweight, but not obese - the 40 pounds I lost then gave me a head start that I never quite lost. Where my father died of weight-related issues at 64, I now have hopes of living a good deal longer.

It may turn out that I’m wrong and that the pop-health fMRI science is right, and that leptin has a good deal more control of this process than I think. But please trust me as much as you can trust an anonymous internet guy here - it’s worth trying. They have nothing like the proof they need to convince you to give up or that your health is predetermined by some ill-defined hormonal destiny.

That got a little preachier than I normally get, so thanks for hanging in there. I’ll be back in a couple days with part 2 of this series, looking at arguments of the “all diets don’t work” variety.

Found a typo at " Lean participants so no effect at any point".

Overall good article. I think the takeaway is that (a) it is really hard to prove that X does Y and (b) Leptin and other hormones are probably more complicated than we think.

Nice post! Minor point - I think that dark matter is on sounder epistemic footing than your passing reference to it seems to suggest. I'd propose dark energy as an alternative physics concept whose epistemic status is more like that which people tend to ascribe to dark matter.

Follow-up thought #1: I'd be interested in reading what you have to say about dark matter/dark energy if you'd be interested in writing about it.

Follow-up thought #2: Dark matter is often used as an example to gesture at the idea of 'a scientific hypothesis which we don't have direct evidence for, but accept because it explains certain observations for which we don't have better alternatives.' Putting aside questions about the strength of the evidence for dark matter in particular, this distinction strikes me as a bit fuzzy - after all, isn't all evidence indirect in some sense? Is 'inference to the best explanation' really so different from however we reason in most cases? There are other modes of reasoning of course, such as theoretical coherence or simplicity, but I'm not sure that's what the dark matter example is usually intended to get at (nor does it seem that dark matter does atypically poorly on those metrics).