Slowly Parsing SMTM's "Lithium is Making Us Fat" Thing

Entry 1 of ?: CICO/Willpower/Habit dismissal

The latest thing making the rationalist rounds is Slime Mold Time Mold’s Chemical Hunger, in which SMTM posits that chemical contaminants of some kind uncommon in the past but common today are increasing obesity rates. Basically, he says, a 1940’s person was thin because that’s the default - it should be effortless to maintain your swimmer’s body. Something else has gone wrong that makes it harder, and by proxy makes us all a little jigglier.

Sometimes when I examine something like this, I’m pretty eager to prove it wrong; in a lot of ways, “prove the other guy wrong” is my default state. This is even more intense of a drive for me when the person is doing something that I think is amoral in some way - that’s when I go into full skull-bashing mode and do my best to prove the other person is some kind evil Loki-type figure who must be resisted at all costs.

My calmer, more normal readers will be glad to hear that’s not really the case here. The biggest reason why is is that this claim is at the very least plausible; obesity rates did rise sharply since the 80’s, and so did the sheer variety of chemical contaminants in the environment over the same period of time. Whether or not he ends up being right, I’m sort of glad to see that someone is looking into the hypothesis; it seems like the kind of thing you don’t want to sleep on.

With that said, there are some potential and actual problems with the piece.

The potential problems I’m dealing with today broadly don’t have to do with the chemical contamination piece of the puzzle. Instead, we first have to look at all the things SMTM thinks the problem isn’t. If this seems arbitrary or unfair, consider something like the entire first quarter of the series is dedicated to eliminating these causes from consideration. SMTM thought it was important to do so, and because of this our first job is figuring out why.

The ghost that moved your keys

A story:

Bob lives in a universe containing exactly one very real ghost. Despite being able to move through objects, the ghost only moves at a normal human pace and can only be in one particular location at any given time. Despite not doing it particularly often, the ghost is also thought to possibly be able to move small objects short distances, although nobody has ever proved it does.

Everyone knows the ghost exists, but beyond that the ghost is completely untrackable; there’s no way to know where it is at any given time.

One day, Bob comes home from a hard day at work and puts his keys down on the right side of his coffee table. He then takes a nap for a few hours and wakes to find his keys are on the other side of the table. Bob is convinced the ghost did it.

Now, it’s completely possible that the ghost moved Bob’s keys; in this universe, that’s very much something that could happen. But since there’s only one ghost, the chances of this are really, really low compared to almost any other option. If Bob told you that the ghost moved his keys, you’d think this was less likely if any of the following was true:

Bob cohabitates with one or more people or has pets

Bob is a restless sleeper

Bob has memory problems, or even just a fallible memory

Bob has a history of exaggeration or lying

All of those are more likely scenarios than the ghost being local enough and motivated enough to move Bob’s keys, but they don’t have to be. Just having alternate explanations is enough; the more alternative explanations there are for Bob’s big key-migration, the less confidence we should have in any particular explanation.

If Bob wants to reduce your ghost-doubt, he’s going to be motivated to eliminate as many of these alternative explanations as he can. So he might point out that he lives alone, that he only sleeps when strapped to a table like the mom from Terminator II, that he took pictures before and after his nap and can show you the timestamps, or that he can prove he has a brain implant that prevents him from telling tall tales.

SMTM has a similar problem and reacts in a similar way. Chemical contaminants aren’t as unlikely as the ghost, but they are about as elusive and hard to prove. At the same time, alternate explanations are a dime a dozen. He’s not unaware that people are going to have a gut reflex to say things like “What if people are just eating more, and/or exercising less?” or “what if it’s somehow corn?”, so he spends somewhere from a quarter to half of his total wordcount addressing these issues and trying to reinforce his hypothesis through deductive means.

Even if he failed to eliminate a single alternate explanation, that doesn’t at all mean he’s necessarily wrong. It’s at least possible he could have strong enough evidence to support his hypothesis without considering any other explanations. But the heavy emphasis on eliminating other explanations at least seems to indicate he thinks he doesn’t, so it’s worth taking a look.

Necessary Context

There’s some stuff you should know going into this discussion. I give you full permission to skim this section; it’s going to be a long article in general and you might want to keep your energy levels up, especially if you are part of the cohort of Hackernews users who reacts with rage when anything is longer than 800 words1.

What CICO does and doesn’t demand

A very bland and defensible formulation of CICO is something like this:

Fat is stored energy, and a pound of fat contains about 3500 calories. It’s also your body’s most efficient store of energy - other types of tissue are much less calorie-dense than fat.

Because energy doesn’t come from nowhere, that means that any fat on your body was created from an excess of calories - at some point you ate more energy than your body needed, and it stored it as fat.

Similarly, if you spend more energy than you take in, you MUST lose weight. That energy has to come from somewhere. Even if you think your body would metabolize other tissues first, their lower energy density means you’d lose more weight, not less (although we don’t recommend this).

This isn’t or shouldn’t be controversial; it’s very basic thermodynamics and there’s no way around it.

While all this is true, there’s still some complexity to be had here. For instance:

Physics doesn’t make as many demands in the world of the thin. While you can’t make energy from nothing, there’s no rules about wasting energy. The presence of “effortlessly thin” people who stay thin despite eating a lot is an accepted enough fact we pretty much know this is happening at least some of the time.

So the presence of fat means you ate more than you needed to at some point and that you haven’t undercut your body’s energy needs enough to make it cut into those stores since. But the opposite isn’t true - a skinny person isn’t necessarily someone who never ate in excess, or who did and then undercut their body’s energy needs. They might just be “lucky” and have a body that hates to be fat.

We are kind of bad at knowing how much energy value food has in the sense of really knowing how much energy your body is getting out of any particular meal. There’s a lot of reasons why, including differences in digestion between individuals, differences in bioavailability between different foods, and even simpler harder to track things like how thoroughly cooked a particular food is when you eat it.

Now, it’s incredibly likely that you just read this and went “oh, I know that - that’s why you can perfectly count your calories and still get fat - there’s more calories than the label says”. But note that even though the headlines say things like “You’ve been counting calories wrong your entire life: The surprising science that might be skewing your weight loss results”, the actual observed effect tends to run the other way - i.e. we might overestimate rather than underestimate the calories in food.

To put it another way: you shouldn’t have any confidence in label-calories, but rather than a 25% error meaning you ate 2500 k/cal instead of 2000 like you thought, it’s as or more likely you ate 1600 k/cal instead.While your body really does have to lose weight if your food intake undercuts your energy needs, those energy needs are not set in stone even if we ignore exercise. Whether or not this actually happens, your body probably has some wiggle room to turn certain energy-consumption knobs down - like maybe if it thinks it needs to it makes you heal a bit slower or depresses your energy levels, or something.

These make for some wacky situations. We can imagine two people who on paper have identical caloric needs - same sex, same size, same body type, same age - who both eat an identical amount of calories we’d expect to make each slightly chubby, and find one gets chubby while the other retains rock-hard abs. And since there are multiple plausible reasons why (Gut flora! Hormones! Ghosts!) it’s really hard to parse why.

The terminal value of an ACX-style rationalist is niceness, not accuracy

About halfway through the piece, SMTM says this:

There’s also a strong moral reason to argue against this aspect of the hypothesis, because the idea that obesity is the result of lapses or weakness in willpower has been used to justify many cruel and ineffective positions. People who believe that obesity is the result of laziness and weak willpower believe that people with no moral fiber can be recognized on sight.

As a result, they do things like treat overweight and obese people with disrespect, make jokes about them, don’t hire them, don’t give them proper medical treatment, etc. They think that shaming and social stigma are effective interventions against obesity. Some think that overweight and obese people should feel ashamed of their weight. This is as horrible as thinking that cancer patients should feel ashamed and responsible for falling sick.

There’s sort of a lot going on here. Note that he doesn’t say there’s a strong moral reason to argue against that aspect of the hypothesis if it’s wrong; he does seem think it’s wrong, but that’s a separate issue and presented as such. There’s a strong implication that your opinion on factual reality should be swayed by how people react to it, that if the implications of a truth are unpleasant that this in and of itself makes it less true2.

I don’t want to make this quote do too much work, however. In the same way that the existence of mean people doesn’t really affect the causes of obesity, SMTM hating the idea that willpower might be a component here doesn’t mean that it necessarily is. He could be completely unwilling to consider willpower no matter what the evidence and it could still be false; desiring a particular reality just isn’t a lever that directly affects truth in that way.

That said, we have to adjust our priors a little bit as we look at his work. He has two big reasons to want willpower and other explanations like it to fail - it would be nicer, and it would reinforce his piece. I don’t think he’s exceptionally bad here, but he’s also probably not immune to incentives. It’s relevant that he’s thinking about this through a lens that views any assumption of personal responsibility to be evil.

A lot of people probably want something like this to be true

If I’m overweight (I am) and I’m to any extent in control of this, it’s fair and accurate to say I could be thinner if I wanted to. It might be really hard or it might involve sacrifices I really shouldn’t have to make, but there’s a whole spectrum from “I could be thin just by wanting to” to “I could be thin if I abandoned all other considerations and all benefits life offered to pursue this one goal” in this conceptual space.

The practical upshot of that is that the harder it would be for me to be thin, the less bad I should feel about being not-thin. If all I needed to do was jog an hour a day, I might be being unfair to my future grandkids by not doing so. If I’d have to abandon my breadwinner role to get six-pack abs then I’m not only not at fault, but I’m actually making good moral decisions for my family.

Just as SMTM above posits that there’s a strawman (or weakman) group that wants this to be a mere willpower issue so they can be mean to fat people, there’s almost certainly a certain amount of us that want any solutions achievable through reasonable actions to be false, for entirely understandable reasons: It would absolve us of all guilt.

This means something for all of us: there’s probably some preferred cause of obesity all of us gravitate towards, and that we’d accept above the others given equal amounts of evidence. I shouldn’t have to point out the propensity for bias here; certainly, most of you already know about it. But SMTM brings up bias in his work in a compelling way but only in one direction - it’s important to counter that somewhat going in.

The actual meat of the article finally

SMTM starts the series by pointing out a series of weird-looking aspects of the obesity problem and calling them mysteries - it is these problems that he will later propose are or aren’t driven by various potential causes.

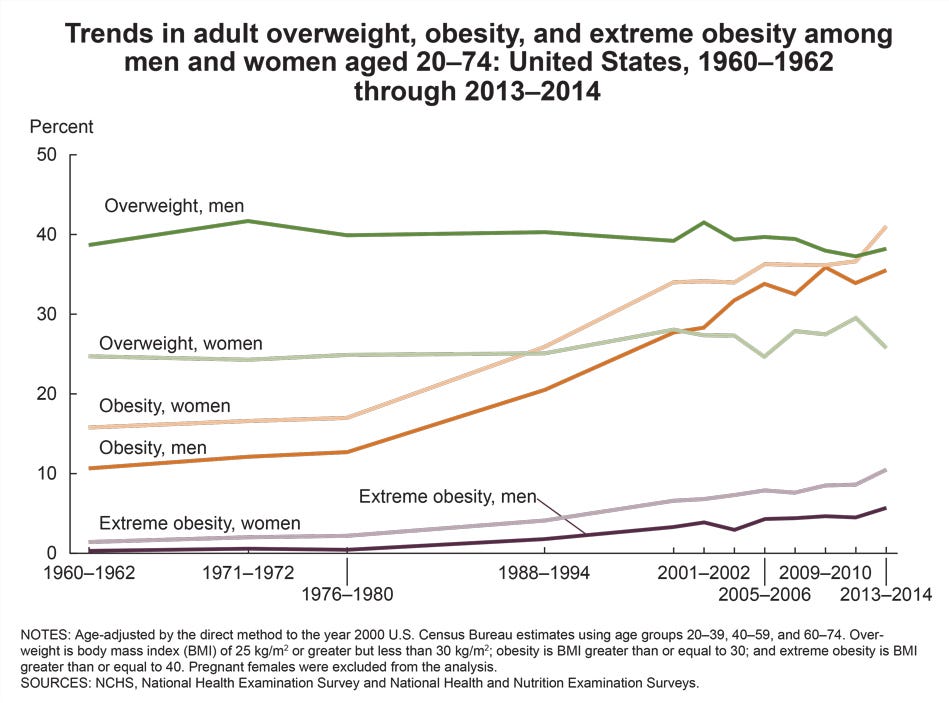

We got obese abruptly. He shows charts like this showing that the better data we have indicates that obesity is sort of a post-80’s issue:

The crisis is ongoing. He points out that we’ve been trying to address the issue and broadly failing:

Things don’t seem to be getting any better. A couple decades ago, rising obesity rates were a frequent topic of discussion, debate, and concern. But recently it has received much less attention; from the lack of press and popular coverage, you might reasonably assume that if we aren’t winning the fight against obesity, we’ve gotten at least to a stalemate.But this simply isn’t the case. Americans have actually gotten more obese over the last decade. In fact, obesity increased more than twice as much between 2010 and 2018 than it did between 2000 and 2008.

Hunter Gatherers aren’t fat, despite eating various diets. SMTM shows some studies showing hunter gathers often have weird diets (high in sugar, high in fat, or high in carbs with limited variety) but don’t tend to get obese. He mentions that the Inuit are obese, but weren’t until western culture found them.

Double entry, both that lab animals and wild animals are getting fatter, and that when you feed lab animals actual store-bought human food as opposed to food you cobbled together to be nutritionally similar to it (a “cafeteria diet”) they get fatter.

People at living at altitude are less overweight. SMTM shows some studies that show people living at high altitudes are obese less often, sometimes lose weight when they move to high altitudes, and notes that there’s not great evidence showing this is attributable to lower oxygen levels (note: this is a really weak statement, since it would be really hard to test. You’d have to put people in a low-oxygen room for months while accurately maintaining their outside-the-room lifestyle, which probably isn’t even possible.)

Diets don’t work. This is the big, important one. Big enough that we need to not only leave this numbered list but also start a new section to address it. The bulk of today’s article is about this.

What does “diets don’t work” mean?

No phrase in the entire obesity-discussion space does more work than “diets don’t work” (hereafter DDW). As far as I know (and this is bizarre, if true) the concept was popularized by this article written by David Wong, formerly of Cracked.com and still the author of John Dies at the End.

The idea is that the mass of data we have shows that diets consistently either fail to make people lose weight at all, or show them not losing enough, or show them not keeping it off. From there DDW, says “there’s no such thing as a diet that works; it’s impossible to lose weight”. So you can imagine a conversation between a CICO person and Strawman David Wong that goes like this:

SDW: Diets don’t work.

CICO: I mean, that’s… what? Of course they do. If you eat less energy than your body needs to operate, it has to get it from somewhere.

SDW: Well, no. We’ve tested that idea. You do a study where you try out some new diet and you find out that people either don’t lose weight or slingshot back to their old weight right after, and this has happened thousands of times across thousands of studies. It’s a disproven concept.

CICO: Well, I mean, it can’t be disproven. That energy has to come from somewhere, or else Isaac Newton has a lot of explaining to do. This just sounds an awful lot like people not actually dieting, somehow.

SDW: Listen, man: I don’t know what to tell you. We’ve tried out your idea a myriad of different ways, and it never, ever works. You can tell me physics demands that flapping your wings hard enough lets you fly, but If I just watched 10,000 people splatter at the bottom of a cliff trying it out I’m pretty justified in doubting you.

SMTM is a modified version of Wong here. He says the following, and there’s a lot to unpack in it:

There’s a lot of disagreement about which diet is best for weight loss. People spend a lot of time arguing over how to diet, and about which diet is best. I’m sure people have come to blows over whether you lose more weight on keto or on the Mediterranean diet, but meta-analysis consistently finds that there is little difference between different diets.

Some people do lose weight on diets. Some of them even lose a lot of weight. But the best research finds that diets just don’t work very well in general, and that no one diet seems to be better than any other. For example, a 2013 review of 4 meta-analyses said:

Numerous randomized trials comparing diets differing in macronutrient compositions (eg, low-carbohydrate, low-fat, Mediterranean) have demonstrated differences in weight loss and metabolic risk factors that are small (ie, a mean difference of <1 kg) and inconsistent.

Most diets lead to weight loss of around 5-20 lbs, with minimal differences between them. Now, 20 lbs isn’t nothing, but it’s also not much compared to the overall size of the obesity epidemic. And even if someone does lose 20 lbs, in general they will gain most of it back within a year.

Attentive readers will note he immediately spins this in a slightly different direction, saying that diets don’t work better than each other as opposed to not working at all. But he then brings it back to saying, hey, here’s some indication diets don’t work. He provides two links supporting this, both of which basically say that most people didn’t lose huge amounts of weight in various studies, even if they lost some.

It’s at this point that I have to explain a little bit about how most studies dealing with diets work. First, they almost always deal with people who are already obese, and are old enough/sick enough to be interacting with doctors regarding their obesity. These people go have a conversation with a doctor involved in this kind of research who tells them to go on a diet. Months later, they check to see if they did, and if they lost any weight by doing so.

Note that if “failure related to making choices” is a legible concept here, it’s relevant that these studies are dealing with groups who are self-selected to have failed in that particular way.

We also live in a world where “losing weight is related to eating less and exercising more” is common knowledge pounded into nearly everyone nearly from birth until death. It’s thus utterly and totally unsurprising that a doctor saying “hey, maybe lose some weight” with no other changes fails to make substantial amounts of people lose weight.

As a for-instance, here’s some exerpts from the abstract of the latter link in the SMTM’s last quote:

Study Selection Overweight or obese adults (body mass index ≥25) randomized to a popular self-administered named diet and reporting weight or body mass index data at 3-month follow-up or longer…

As described in a protocol outlining our study methods,8 we included RCTs that assigned overweight (body mass index [BMI; calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared] of 25-29) or obese (BMI ≥30) adults (≥18 years of age) to a popular branded diet or an alternative. We included RCTs that reported weight loss or BMI reduction at 3-month follow-up or longer…

We included dietary programs with recommendations for daily macronutrient, caloric intake, or both for a defined period (≥12 weeks) with or without exercise (eg, jogging, strength training) or behavioral support (eg, counseling, group support). Eligible programs included meal replacement products but had to consist primarily of whole foods and could not include pharmacological agents…

Exercise was defined as having explicit instructions for weekly physical activities and simply dichotomized when differences between varying degrees of exercise frequencies appeared to have negligible effects. Diets with at least 2 group or individual sessions per month for the first 3 months were considered as providing behavioral support.

You might note that this is suspiciously like assigning someone a diet and sending them home without any monitoring to see if they do it. But here’s another important thing:

These findings support recent recommendations for weight loss in that most calorie-reducing diets result in clinically important weight loss as long as the diet is maintained.

And here’s a quote from the first link SMTM provided:

There are 2 reasons the diet debates persist. First, the commercialization potential of breakthrough diets is substantial. Fad diets have created a multibillion-dollar industry. The difference between fad diets is almost entirely related to macronutrient composition (eg, Zone, Atkins, South Beach, Dukan, Paleo). A second factor is the assumption that lifestyle interventions are ineffective. Poor adherence (and consequent weight regain) following the intervention is cited as evidence that these interventions do not work.5 This conclusion can be challenged because it assumes a definition for efficacy more stringent than that applied to other forms of preventive care.

Termination of treatment or nonadherence almost always results in reduced benefit. The effects of cholesterol-lowering agents, hypertension drugs, and diabetes medications do not have long-lasting effects after patients stop taking them, with effects declining within a matter of hours (eg, metformin) to months (eg, statins). Just like medical therapies, behavioral interventions should only be expected to be effective when treatment is active.

In both cases, the study authors say “Hey, check it out - diets do work, so long as people do them”. So SMTM is sort-of-kind-of-correct to say diets don’t work, but only in the very specific sense that he might mean something like this:

When people who are already obese and are by nature of that likely demonstrating a history of failing to diet or failing to adhere long-term to any lifestyle intervention of any kind (since they all work about the same) are assigned a diet, they usually don’t actually follow it.

That means public health has limited ways to force people to lose weight, whether or not the diets would work if people did them for a long time.

Note that he didn’t say that shit at all; he would have had you walking away thinking that we had great data on what happens when people actually diet, as opposed to when people are told to diet. The study authors mention the distinction as significant in both sources, and he ignores it. Do you feel ill-used? You should.

But even so, the point-he-wasn’t-making from the last quote box is important, because we can still imagine situations in which “people fail to diet” has a cause besides “some people are weak”. If SMTM’s chemical-cause theory is right, it might just amp some people’s hunger up to 11 and make them fail where people of similar willpower would succeed.

Miscellanious claim roundup

Some of these claims that come next are wrong while others are merely overreaches. I’ll leave it pretty open for interpretation where I can, but observed incentives + representations that are either sloppy or misleading means I have to look at every claim he makes. So here we go:

SMTM claims:

First, we want to present some common-sense arguments for why diet and exercise alone don’t explain modern levels of obesity.

Everyone “knows” that diet and exercise are the solution to obesity. Despite this, rates of obesity continue to increase, even with all the medical advice pointing to diet and lifestyle interventions, and a $200 billion global industry devoted to helping people implement these interventions. It’s not that no one is listening. People are exercising more today than they were 10 or even 20 years ago.

SMTM means:

This is a survey of how much people say they exercise that doesn’t stretch back into the pre-80’s non-obesity period and so can’t compare in a way relevant to the conversation he’s having, and only looks at intentional cardiovascular exercise during leisure time and not at any more general measure of how much people move around overall.

Again, not worthless, but again, presented as stronger evidence than it is.

SMTM says:

It’s true that people eat more calories today than they did in the 1960s and 70s, but the difference is quite small. Sources have a surprisingly hard time agreeing on just how much more we eat than our grandparents did, but all of them agree that it’s not much. Pew says calorie intake in the US increased from 2,025 calories per day in 1970 to about 2,481 calories per day in 2010. The USDA Economic Research Service estimates that calorie intake in the US increased from 2,016 calories per day in 1970 to about 2,390 calories per day in 2014. Neither of these are jaw-dropping increases.

SMTM means:

Neither of these are jaw-dropping increases, but he’s going to go ahead and treat this average of how much people eat as inferred second-hand by food availability as if it’s confirmed to be evenly distributed among the population as opposed to some people perhaps eating more than others. He’s saying this despite in a later chapter mentioning that:

Obese individuals generally burn 3000+ kcal/day, and while not every modern person is obese, it does make the increase from 2,025 calories per day in 1970 to about 2,481 calories per day in 2010 look relatively small.

Which means it’s very much not evenly distributed, and not only has every possibility of not being a “small” increase for some, but is confirmed not to be by the very existence of the obese.

There’s no mention combining with less overall exercise (as mentioned as possible before) to be a larger net increase in surplus calories. Is it a possibility within the data he’s shown? Yes. Is it definite? No. But SMTM is consistently looking like he’s finding sources that support him and not being particularly critical before using them. They aren’t worthless; they are in fact data. But he’s stretching too much to get what he needs from them.

SMTM says:

The great-grandaddy of these studies is the Vermont prison experiment, published in 1971. Researchers recruited inmates from the Vermont State Prison, all at a healthy weight, and assigned some of them to eat enormous amounts of food every day for a little over three months. How big were these meals? The original paper doesn’t say, but later reports state that some of the prisoners were eating 10,000 calories per day.

On this olympian diet, the prisoners did gain considerable weight, on average 35.7 lbs (16.2 kg). But following the overfeeding section of the study, the prisoners all rapidly lost weight without any additional effort, and after 10 weeks, all of them returned to within a couple pounds of their original weight. One prisoner actually ended up about 5 lbs (2.3 kg) lighter than before the experiment began!

Inspired by this, in 1972, George Bray decided to conduct a similar experiment on himself. He was interested in conducting overfeeding studies, and reasoned that if he was going to inflict this on others, he should be willing to undergo the procedure himself. First he tried to double each of his meals, but found that he wasn’t able to gain any weight — he simply couldn’t fit two sandwiches in his stomach at every sitting.

He switched to energy-dense foods, especially milkshakes and ice cream, and started eating an estimated 10,000 calories per day. Soon he began to put on weight, and gained about 22 lbs (10 kg) over 10 weeks. He decided this was enough and returned to his normal diet. Six weeks later, he was back at his original weight, without any particular effort.

In both cases, you’ll notice that even when eating truly stupendous amounts of food, it actually takes more time to gain weight than it does to lose it. Many similar studies have been conducted and all of them find basically the same thing — check out this recent review article of 25 studies for more detail.

Overfeeding in controlled environments does make people gain weight. But they don’t gain enough weight to explain the obesity epidemic. If you eat 10,000 calories per day, you might be able to gain 20 or 30 pounds, but most Americans aren’t eating 10,000 calories per day.

SMTM doesn’t consider:

SMTM notes here that in a couple weird/informal/old studies some people gained weight slowly, or didn’t gain as much as you’d expect from the excess. There’s no real problem here from either of our perspectives - again, physics doesn’t care if your body shits out extra calories instead of making them into fat; that’s not the energy-imbalance directionality physics chooses to make demands.

But then he does two weird things:

He acts like it’s very weird that people who were previously weight-stable at a particular caloric intake return to that same weight-stable point once they return to that particular intake. But unless I’m missing something weird, could it be any other way? At the very least for this to not happen a person would have to have significant and permanent metabolic adjustments.

He acts like a weight gain of 10-ish pounds a month is small, and tries to hide that 20-30 pounds over a few months is massive weight gain by saying stuff like this:

Overfeeding in controlled environments does make people gain weight. But they don’t gain enough weight to explain the obesity epidemic. If you eat 10,000 calories per day, you might be able to gain 20 or 30 pounds, but most Americans aren’t eating 10,000 calories per day.

Both of those are bad. In 1. he’s using careful phrasing to make normal-seeming, logically implied stuff look weird. But it’s not clearly weird that eating a caloric intake that had reliably kept you at a certain weight would reliably return you to that weight.

It might still be odd if you make a ton of other assumptions, but he’s not stating those assumptions here - he’s just saying “look, it’s bizarre that a diet that historically held you at a certain weight would hold you to that weight” and leaving it at that.

#2 is worse, though. He’s telling you that a weight gain pace of 120 pounds a year is small, so he can just paper over it and ignore it from now on. Why? And it’s not the only place he’s weird like this:

All diets work. The problem is that none of them work very well. Stick to just about any diet for a couple weeks and you will probably lose about 10 pounds. This is ok, but it isn’t much comfort for someone who is 40 lbs overweight. And it isn’t commensurate with the size of the obesity epidemic.

See how he’s disregarding time again? 10 pounds over two weeks is 40 pounds over 2 months. That’s suddenly a lot of comfort for the person who is 40 pounds overweight, right? Is it more complex than that, and people would have to probably adjust their diets as they lost weight to keep the returns steady? Sure. But it’s absolutely bizarre to have someone look at you and say “Listen, you can lose 10 pounds over two weeks. But that’s the max - you can’t diet longer than two weeks. It’s two weeks or nothing.”.

This is also an isolated demand for vigor - at no point does he look at the rate people who end up obese gain weight and say “well, they only gain 30 pounds a year or so; it’s impossible for them to become fat”. It’s just a weird, bad look; it’s the look of someone who wants something to be true and will accept anything that kind of indicates it.

So I want to take the time to be very, very clear: Nothing I’ve said here disproves SMTM’s Theory3. Could chemicals be the cause of your obesity? Sure they could. Anything is possible, and something has to account for the obesity epidemic.

But the pool of potential somethings you consider is important. If we wanted a hypothesis like “since the 80’s, food has gotten much better, and so has TV. It’s possible the increased reward of both things has out-performed other more energy-negative activities, and that’s why people are fat”, we could also consider that plausible. There’s dozens of similar eating-more-exercising-less theories we could consider.

SMTM says none of them are enough, but every place we’ve looked so far he’s stretched really far to make very confident statements on limited evidence (sometimes even evidence the authors of the papers said contradicted his point). So where we look at any of his other arguments, we have to discount everything we’ve talked about so far; there’s just not enough there that we should adjust any of our priors.

At 5.5k words, that’s it for today. I’m not sure how many entries it will take to examine the whole series, and I’m also not sure I’m going to do them all in an unbroken chain. Buckle up; it’s going to be a long ride.

I like Doc Hammer’s blog, though I keep forgetting to link to it. It’s good!

Hackernews is filled with smart people who accomplish things. Good folk. I’ve had a lot of success there and I’m thankful for it. For some reason it’s also home to a cohort of people who will look at an article they just read that’s #1 on their site and say “someone should tell this guy he’s never, ever going to get people to read his stuff if it’s not much shorter”.

This is actually a really consistent argument technique over a lot of different domains. Everyone basically knows on some level that something having bad implications doesn’t make it less true in and of itself, but it’s really common for someone to say “Listen, man, even if you are right, doesn’t being right make you a bad person? Wouldn’t you rather join us on the side of conditional truth based on social acceptability?”

When I first started writing the blog, one of the first things I talked about was Matthew Yglesias saying this, about rationalists in general:

In the (liberal, coastal, urban, very political) circles that I travel, everyone (especially parents) knows and acknowledges that men and women are, on average, different in ways that end up mattering for the distribution of outcomes. But everyone also believes that sexism and misogyny are significant problems in the world, and that the people struggling against those problems are worthy of admiration and praise. So to leap into a conversation about sexism and misogyny yelling “WELL ACTUALLY GIOLLA AND KAJONIUS FIND THAT SEX DIFFERENCES IN PERSONALITY ARE LARGER IN COUNTRIES WITH MORE GENDER EQUALITY” would be considered a rude and undermining thing to do. This is just to say that most people are not rationalists — they believe that statements can be evaluated on grounds beyond truth and falsity. There is suspicion of the guy who is “just asking questions.”

The entire tone of the piece where it intersects truth is something like “look at the silly people who think something being true is important; they don’t know when all the cool people at the party would know that the only truth is social coolness, like me!”. It’s weird to know Yglesias is taken seriously when his apparent stance is something like “listen, there’s gonna be times I lie to you so I can hang out at the right parties - don’t be a rube about it.”.

I think there’s a value in watch-dogging the work of others; it’s pretty much the main reason I write about serious stuff at all. With that said, it’s really easy to go “this guy sucks, he’s a bad guy, everyone should hate him” without justification. In this case, I think SMTM actually made an interesting piece that overextended; not only might I be wrong, but I don’t think it’s a mortal sin even if I’m right.

I don't have a stance on the DDW thing, but I think this is a pretty uncharitable framing of that take:

> You can tell me physics demands that flapping your wings hard enough lets you fly, but If I just watched 10,000 people splatter at the bottom of a cliff trying it out I’m pretty justified in doubting you.

An example of a way in which CICO might not be exactly true is if there's a fat thermostat or whatever SMTM calls it, and people are subconsciously changing their rate of calorie usage (fidgeting, or becoming restless and moving around, or even just being warmer/colder) when their body is lower/higher on fat. Then it's still literally true that it's calories in/calories out, but the calories out part is harder to modify than you'd expect since your body is fighting against you. Similar is if people's hunger pangs kick in at different points, it's still calories in/calories out, but an overweight person starts suffering if they eat 2k calories and I basically feel fine.

I wish I'd recorded the citation, but I read a few years ago that someone tracked weights in a population over time. I think they found that those who became obese did it at a rate of around 100 excess calories (i.e., KCal) per day. Seemingly not a lot, but compounded over months, years...

Also, I think it is important to note that the mechanism for metabolizing alcohol and refined sugar is different than most other calories. They must be processed by the liver. There is a fair amount of evidence that Type 2 diabetes is the result of years and years of pushing the liver to metabolize more of these substances than it evolved to handle (e.g., leading to fatty liver, pushing sugars back into the blood stream, weight gain, and diabetes). "Researchers examined five nationally representative surveys about food intake in the U.S. from 1977 to 2010, and found that added sugar consumption by American adults has increased by about 30% in the last three decades."

Could the mystery be as simple as refined sugars and a more sedentary lifestyle?