I once wrote an article about being poor, and I started it out with a story about a friend who had spent some time explaining to my wife (who, at the time, was struggling to maintain a household of four on entry-level retail money) how hard up for funds they were, and how stressful it was. The zinger of the story, such as it was, was that the woman and her husband were both doctors. They weren’t bad people, but they came from a context where things like “being broke” had entirely different meanings.

Then (and now) I didn’t begrudge them the opportunity to talk about their stress; I’m sure their negative feelings about their worries were real. The tricky thing about hardship is that people tend to perceive all their troubles relative to the worst kind of problems they’ve experienced. I sometimes complain about being sore after doing a moderate, almost non-existent amount of exercise. I’m sure at some point or another I’ve done this to a person who ran marathons. And if so I probably was sore, but only judging by the standards of my personal frame of reference.

There’s all sorts of terms and experiences I’m sure I could apply this to, but right now the one that interests me most is the phrase a shitty job. I recently transitioned from having lived my whole life doing the kind of jobs you could do with zero day’s training and no developed skills. I’ve heard the phrase (and some classier high-end equivalents) since then, but it’s used much differently; it’s describing a different set of worries as experienced by a different kind of person living a different sort of life.

Wages, Non-Work Survival Stress, and You

I once worked a temp job related to paying out settlement money, a class of work that’s sometimes called class action lawsuit administration. The work mainly involved examining an endless stream of documents and was, as a result, immensely boring. For reference, imagine looking at the same line on an endless stream of mostly-identical documents, pushing either an “accept” or “reject” button, and then repeating this process hundreds or thousands of times over eight hours.

I mentioned the massive boredom of this process to a coworker at some point, and they looked at me like I was crazy. This is a wild paraphrase, but their response was something like this:

What are you complaining about? I don’t care if they want me to lock myself in a closet and hit myself with a brick for eight hours. I’m doing it. It’s so much money.

The crazy amount of money in question was $18 an hour.

If it sounds weird that this amount of money would be enough to convince anyone to do anything they had a particular distaste for, consider that the person in question had previously never made more than $14 an hour. Annualized, it was the difference between $28,000 and $36,000 a year. $8,000 might not seem like a huge absolute increase in pay, but for the subject of the story it was almost a 30% raise.

At a level where you are barely managing (or failing) to pay your bills, something like that might mean the first disposable cash you’ve had in months. The same decrease might mean not being able to pay rent. So while I know for a fact there are income levels where $8000 a year is negligible, there are also income levels where even an extra dollar an hour is the only thing you can reasonably consider; it’s potentially the difference between not surviving, surviving, or building up a (very small) buffer between you and disaster.

Now consider that real people are sitting around right now bemoaning the fact that to do the kind of work they want, they’d have to take a very significant pay cut - say dropping from $100,000 a year at an established company to $80,000 a year at a high impact startup, or from $150,000 at a soulless big-corporate job to $120,000 anywhere with even a speck of fun in the job.

I don’t want to minimize this complaint, because it’s real and it sucks. But it’s a fundamentally different kind of decision when all the necessities are covered, recovered and insulated from risk by an “oh-shit fund” of some kind. Would you take that big, soulless corporate job if it was the difference between being able to buy your kid’s clothes or not? Of course you would. But neither I (at the moment) nor most of the people reading this are playing with those kinds of stakes, so they get a little more freedom in how they choose their work without risking keeping their progeny shod.

At the time I was working in settlement claims administration, I had never decided to accept a job offer using any parameter but pay in my entire adult life. In the case of that particular job, that meant working for the least-good employer I ever had1 and doing some boring stuff. It wasn’t great, but it also wasn’t that bad; I didn’t die or anything.

Later on (as I accumulated increasing amounts of work experience) I found there were even more severe tradeoffs to be made. Even the skill-and-credential-poor can often work their way up to more money if they are willing to make even more severe tradeoffs in the bargain.

Meatgrinder Jobs

There’s a couple of ways to think about how difficult a job is. The first way has to do with the amount of training or ability the job requires, as opposed to things like hours or stress. No matter how hard of a worker you are, you can’t just walk in off the street and do brain surgery; the job is difficult in the sense that not a lot of people can do it, full stop.

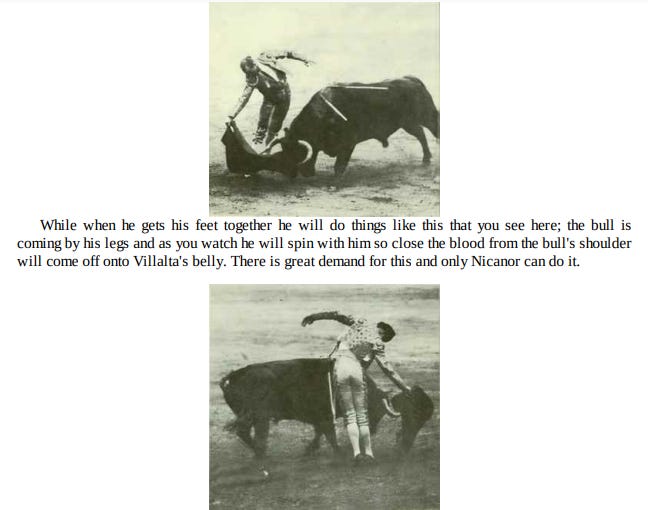

The same goes for job titles like “software engineer”, “pilot”, or “cake decorator”; whatever other difficulties the job may have, the primary hurdles are ones of skills, talent and training. It’s a bit like this, from Death in The Afternoon:

All those jobs are hard in the sense that it’s difficult to do them at all, but that doesn’t tell you a lot about the day-to-day hassle of actually performing the work. There are at least some cases where the work itself isn’t hard at all, like the software engineer who reveals he only works 10 honest-to-god hours a week, or the bullfighter above who (presumably) was only significantly taxed in his once-a-week-bullfight and the week-long bouts of Spanish lovemaking bracketing it.

But say you don’t have skills, talent or training and you still want to make a decent-ish wage of, say, 40-45k a year. There’s still options for you, and they come in the form of jobs that require a slightly elevated level of pay to get anyone to do them at all due to some well-known associated misery. As the header of this section implies, I think of these as meatgrinder jobs.

A meatgrinder job is a job that pays more not because there are fewer people who can do it, but because there are fewer people that will. They have insanely high turnover, because some aspect of the job is so bad that the vast majority of people who try it don’t stay. Maybe it’s long hours that never stop or maybe it’s constant on-call work. Maybe it’s an insane, stress-intensive workload you can’t begin to keep up with.

I’ve worked two of these kinds of jobs, the first as a Claims Adjuster for a big auto insurance company, and the second as a mortgage processor. Again, these are the opposite of the bullfighter-job; anybody can do them. But both were situations where the unspoken assumption was minimum 50-hour workweeks at an intense regimented work pace just to begin to keep up. Where there was more work to be done, your hours wouldn’t be explicitly adjusted but your workload would; 50 hours would often become 60 or 70 (or, in my case, I’d just fall further and further behind pace to worse and worse manager reviews).

Two guys had heart attacks while I was at a single one of those jobs, and I ended up getting stress-related health problems before I was done with either. So why not leave sooner? That sweet, sweet cash. Claims Adjusting was a 43k a year job at a time when my next closest pay had been something like 32k; mortgage processing, the harder to get of the two jobs, was ~60k.

I’m very admittedly a fragile sort of personality and neither lasted long. But it still took blood-in-the-toilet level stress to get me to quit either job, because while I had them I was able to become so enviably rich as to be occasionally able to spring for McDonald’s for the family. Money is a powerful, powerful motivator here and if Mortgage Processor or Claims Adjuster is the best job title you can get, the next steps down in not-having-cardiac-events territory are often jobs that pay 25-50% less.

Note that all this is about how the jobs are designed, not how they treat you when you are there. For that, you need to look at another aspect that I’m not sure is as common in low-level jobs as it is with their good-job brothers.

When they know they’ve got you

Some of the things I’ve talked about so far aren’t entirely unique to bad jobs, as I’m sure you’ve noticed. Somewhere there’s a real estate agent or a lawyer working for a big firm reading this, and I’m sure they are fuming; those are both jobs that are at least pretty hard to get into which then also make huge, huge stress and time demands if you want to make it big. I haven’t lived every life; don’t think I’m minimizing anything you go through.

But some things I think really are somewhat unique to the lower levels of jobs. The first is directly related to how hard a particular employee is to acquire, and how hard the employees at a given company are to acquire in general. If your company hires a lot of hard-to-get employees, there’s a good chance they have a variety of benefits designed to make the job more appealing beyond the pay - good insurance, lots of time off and other things of that nature.

This also filters down to less formal benefits. If your company worked really hard and spent a lot of money acquiring particular pieces of talent, they notice when those pieces of talent leave the company. Scenarios like a nightmare manager who drives off good people are less likely to be allowed to be permanent problems. Cultures of respect (or at least feigned respect) are built.

Note that in these companies you don’t often have to be the most valuable employee in the world to get these kinds of benefits; the company often can’t maintain two separate cultures or find ways to short-change only some of their employees. If you are a really hard-to-find talent who is working at a particular place because they lured you in with incredible benefits, feel good about that; you probably played a part in making sure someone less vital to the company’s plans got them as well.

But as standard as this kind of logic seems if you’ve only experienced good employers and employment, incentives matter. Employee longevity has real costs in terms of both funds and efforts. I’ve worked in multiple places where the highest-paid employees made less than 50k, and nobody was any harder to replace than an ad on Indeed and a few interviews to make sure they weren’t drug addicts. In that case, there’s very little countering the costs of making sure employees stick around.

Some employers will “do the right thing” here even if the business math doesn’t add up, but most won’t. That often means shitty offices in scary parts of town, insurance plans of the type that are intended not to be utilized, some minimum amount of vacation time you aren’t really allowed to take, and so on. If the risk to the company of you leaving is low, the company reacts in kind and slashes whatever costs they can - after all, they could have another person in your low-skill seat in a few days.

I’ve seen things like people who couldn’t afford temp-company high-copay insurance being fired for taking a sick day without producing an official doctor’s note. They were obviously sick (and had been working sick), but the demand was that their flu be bad enough to keep them from working but somehow mild enough to make going to the doctor make sense, just to get a note to force the hand of a manager who already knew they were ill. If this seems like the kind of thing you’d lawyer up for, it should, but that also means you can afford the costs of getting a lawyer involved and that you come from a world where lawyers are normal front-of-mind resources.

Was that productive for the company? I never felt it was. But it whipped a bunch of other people into line, at least temporarily, and the worst sting the company felt was hiring two people to cover their turnover that week instead of one.

Low-level coworkers and small-business owners are both a dice roll to work with

OK, so here’s something you won’t hear from other woe-is-me poor people articles: on average (note the italics and the bolds indicating I really hope you read carefully here) low-skill workers are worse in a lot of ways than high-skilled people. Everybody in the low-pay world knows someone who is working a low-pay job who seems like they deserve much, much more, who holds the whole company together and who has just had a lot of bad luck.

But for every one of those ill-fated wunderkinds, there are a dozen people where you look at their situation and go “yup, that makes sense”. There are tons of people for whom employability in any capacity at any pay is surprising; there are people who are always, always about to fly off the handle. $15 an hour IT guy is trying his hardest, God bless him, but there’s a reason he’s that and not $30 an hour network engineer.

If you are $120k a year SE and play your cards right, you can sometimes maneuver into a situation where your coworkers aren’t just competent-on-average but actively bright, sometimes brilliant people. At $35k, usually you are trying to identify the one other person in the office who also got unlucky so you can be friends with someone who isn’t getting remarried a month after their fourth divorce.

Bosses at that level can be weird as well. A small business owner is a funny thing; sometimes they are really incredible people who are all-around competent to an insane degree. Often they are incredible at people skills, in a way that means they are sympathetic/helpful/understanding, and back that with all the powers that being lord of their own domain brings.

I can’t emphasize how incredible it is when someone walks in and goes “Hey, there’s really nothing productive left for you to do today. I’ll still pay you, but you might as well go home”. But for every boss that’s capable of that in addition to running a business, you get bosses who are something else.

Maybe it’s a really, really good air conditioning repair guy who just got too much business to service himself, who has no idea how to run a business but manages to make the paperwork parts work with a little bit of dedication, a whole lot of weirdness, and an extra helping of hoping the IRS never checks on anything. Or maybe it’s the opposite and you’ve got a business school graduate who bought their way into a turnkey operation, understands all the nuts and bolts of the financial operation, but doesn’t know if driving a nail takes a few seconds or a few hours.

Those are just hypothetical examples, but here’s a real one: I once had a boss who became a boss by finding a niche market that didn’t have online stores, creating the first online store for it and becoming a millionaire being “the only guy” who sold the expensive, important things his customers had to have. The wrinkle turned out to be that he did this all from a point on the autism spectrum that severely limited his ability to model the minds of others and communicate effectively.

I worked for him for months as an executive assistant and had to almost beg him to give me direction. I’d eventually squeeze a few priorities out of him, get those done and then end up sitting around with nothing to do. Or I’d complete a task for him, and then find out I had done something completely different than what he wanted - he hadn’t told me enough for me to know what kind of results he expected to see, but assumed everyone’s mind worked a lot like his and I’d figure out the (mostly unrelated to what he asked for) differences myself.

In a big company, he and our hypothetical AC guy would have never made it to middle management, and because of that you see problems of this sort a lot more rarely in that world. And even then, it’s not as if nothing bizarre ever happens in “normal high-skills” type jobs, or that nobody incompetent ever sneaks past the filters. But the variance in the low-end jobs seems a lot higher; weirdness is everywhere, but outliers are much more common at 30k than in a safe, upper-middle-class gig.

(Author’s note: Please know I’m not making fun of any of these people; not everyone has super-marketable skills, and I’m a big proponent of people seizing as much success as they possibly can. I’m certainly not more normal, and it’s only through a lot of weird luck I’ve outdistanced my former coworkers. I’m not looking down on anybody, and I’m desperately hoping that drawing this picture isn’t going to read in a way that suggests that).

In the last article I wrote about poverty-life, I tried to emphasize that I wasn’t trying to make anyone feel bad, and that’s true here as well. I’m trying to draw a picture of a life I’ve had access to that you might not know about, and none of this is intended to imply that I don’t think the complaints that stem from good-paying jobs aren’t legitimate.

I’ve just started to have access to the better-paying-job-world, and I’ve seen some real and legitimate issues. I mentioned a scenario above where people were forced to choose between interesting work or boring, rote work at a significantly better rate of pay. That’s not an easy decision to make! I’ve seen people struggling to decide whether or not to take an interesting job at an interesting company where they felt they could make a difference, only to have to decide against it because the decision would come with too much new-company risk. That’s not a fun choice.

That said, the world I’m living in now really is much different. I don’t think I could point a finger at a truly incompetent coworker; most of the time I suspect that if our chain has a weak link it’s probably me. I have time off I can actually use, and insurance that’s actually intended to be used. It’s not without weirdness, but the oddities are pretty benign.

And it isn’t as if the low-end jobs didn’t have their good side. I got to meet a bunch of really interesting people, people who had done weird things, seen a lot of shit and come out the other side with some stories I’m glad I heard. I got to hang out in environments where professionalism hadn’t covered up all the realness in how people interact, and by virtue of that have had a lot of friendships at work I’m not sure I would have found in more conventional workplaces.

With that said, I also can’t ignore the downsides. Beyond the pay, I’ve had people say things to me and do things to me that I still seethe about. I’ve been treated badly in ways that I still think about a decade later, and in the moment had to swallow it down with no response because the absence of even a week’s pay might have meant an eviction notice.

I was talking to the owner of a small business I frequent the other day about how it’s sort of hard for me to judge someone who doesn’t go above and beyond at a $12 an hour pay rate. That’s not a wage that gives you access to a decent home, quality food, health care or most of the other hallmarks of the kind of life most of us take for granted.

After several minutes, I realized she wasn’t capable of understanding the point; she had good jobs until she had a good business. She hadn’t had the chance to build up the kind of resentment and wariness bad jobs and bad bosses bring. She thought that she’d do a much better job at the same pay rate, and I’m not sure she’s wrong - she’s an intact person in most of the ways what I’m describing breaks you.

To the extent I wish this article would be anything beyond a fun read, I hope it enables some people to consider kinder possibilities. Often a person who can’t or doesn’t hold down jobs very long really is lazy, but every once in a while you find that it’s a person who got fired for having a cold or someone who had to leave a job because they had less-than-superhuman stress resistance. Maybe someone who was going to judge someone for whining about a job they weren’t willing to leave might realize they really can’t leave it, sometimes due to a distressingly small difference in wage.

To anyone who is still stuck in that world, keep trying. I’m not going to tell you it’s sure or easy that hard work will get you out of there. But better worlds do exist, and I’ve been blessed enough to get there, even if it ends up that it’s temporary. Work is still work. Not all of it ends up being good. But keep pushing towards the light at the end of the tunnel; it’s worth it.

The company in question was called Ricepoint, which is connected in some way I never really looked into to a larger company called Computershare. Ricepoint itself (or at least the division we worked for) was a Canadian-based company, and the particular Canadians we worked for were universally contemptuous of every single person on the project, mainly because they were poor/low class.

Sometimes this just meant weird kinds of disrespect you wouldn’t see in other places. Once, I was copied on an email where someone had pretty clearly misread the court order attached to the lawsuit, and was recommending a policy that (were we to follow it) would be in direct conflict with the court order we were administering. I didn’t recognize any of the names on the email, but the sender was directly asking for feedback on the change, ASAP; not answering it would potentially mean getting canned, so I did.

It later on turned out one of the higher-ups had CC’d me on accident and was enraged that I replied. I wasn’t there, but her (unconfirmed, unrecorded) statement on the subject in a subsequent meeting (as relayed to me verbally later) was “I don’t want any of these fucking retards to ever talk to me ever again.”. At the time I had little to show in terms of proof of my mastery of the language, and she sure as hell wasn’t going to take correction from some filthy poor.

(For the record: I’m not usually one to grind the whole “rich people being mean to poor people” angle of the poverty subject. Mostly that’s because most rich people I’ve known have been nice/respectful to me, to the point where I have a hard time even thinking of other examples to share.

The normal unreliable-memory-of-years-ago and bias-of-the-fired warnings should be taken here, but these people were uniquely and intensely bad in a way that defies my entire lived experience. This also made me subconsciously biased against Canadians in a way that took me a while to notice, I fear I’ll never entirely shake off, and I have to actively correct for every time I meet a new member of the snow-British.)

The same company was also never able to set a firm date at which the project was going to end. For a temp, this is actually really bad news – it’s hard to change jobs, and without a firm stop date the incentive of slightly higher pay meant that most people were playing a risky game of staying on with a job that might fire them at any time to try and avoid transitioning back to lower levels of poverty.

As the project went on, some people got worried and started to bail for other jobs. To try and forestall this, the company started having meetings in which they assured the workers they would give them as much notice as possible before the project ended. Thus, in their telling, there was no reason to do anything crazy like quit prematurely – they’d work to make sure there was pivot time.

One day, they were waiting in the office when everyone came back from lunch and fired everyone on the spot, with 0 minutes and 0 seconds’ notice. Have you ever seen dozens of people stunned and broken people, some bawling their eyes out in their cars? Ricepoint/Computershare has, and that same witch from the last story was grinning, visibly proud of the big favor she had done all of us.

Hi Y'all! I'm very glad to have you. Greetings, HN readers good to see you again.

I apologize for being a bad host; I usually respond to all or nearly all comments, and I will do so here as well. But it's going to take me a little bit - I'm trying to keep priorities straight on the most important religious day of my religion's calendar, which means ignoring you for a bit.

Post any questions, comments or complaints and I promise I'll respond within the next day or so.

I’m sort of embarrassed how cheesy this sounds: I grew up pretty well off, but once I turned 14 my parents made it a requirement that I started working. I painted fences, was a barista, did golf course grounds work, and then concrete.

Over a decade of comfy software engineering later I still think back to those jobs. A little overtime is nothing compared to shifts that start at 4:00am. An annoying manager is way better than grumpy women wanting lattes. All my problems of the past decade combined don’t come close to a single day doing concrete in July. Holy shit is concrete hard.

I’m so lucky to be doing what I do. Great post.