Meta-Note: The more observant among you have noticed I put a new section up on the blog. It’s called RC Advice, and it’s mostly just a place you can ask me for questions, advice, a friendly ear or whatever. I’m going to answer every comment in there at least until it gets time consuming enough that I can’t keep up with it. I have it set so when I post in there you won’t get an extra email, so unless I messed something up it shouldn’t be bothering you when you aren’t in need of it.

Some things just feel untrue. For instance, remember the more extreme versions of the "food desert” story? There were millions of people getting robbed of healthful food by evil capitalists who for some never-discussed reason were willing to sacrifice millions of supposedly eager-to-pay customers and all the associated profit for no personal gain. It’s only believable if you have a special kind of logic that only checks to see if things sound cool before deciding they are true. Predictably, any time you check to see what was actually going on you find the truth is pretty much anything but what they said it was.

I’m not sure how often this untruth-detecting radar actually works for me (I don’t keep a spreadsheet, although I should) but I can tell you that nothing trips my hippy-logic detector more than the concept of Walkability, the idea that neighborhoods and cities both can be measured in terms of how easy they are to traverse on foot and should be optimized to maximize the same metric. It’s too perfect; it’s too easy. It’s the exact kind of thing that sounds good enough that nobody ever questions it in any real way, and then I look up ten years later and there’s a law going through congress forcing my wife to wear a beret and buy (but never drive) a smart car, or something.

The entry-level sales pitch for the concept is pretty simple. If you go to almost any “what’s walkability?” article on the internet, you get hit with pictures like this:

Source: "Cobblestone streets in Beacon Hill area of Boston." by denisbin is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0

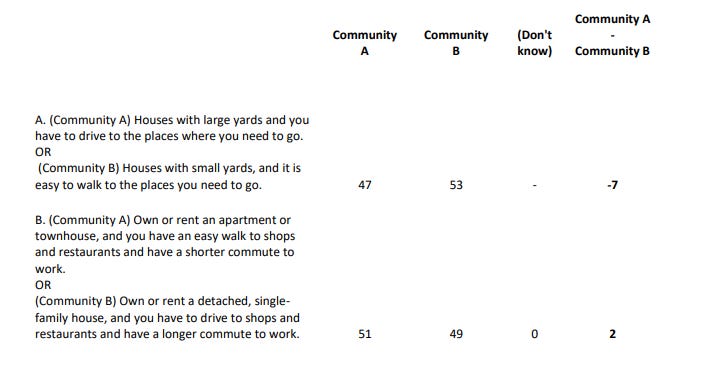

You wouldn’t expect anybody to not want that - it’s literally as pretty as a picture. You can practically smell the handmade scones baking just around the corner at some charming corner bistro. At least on the “asked about it in a survey” front, most people like the idea of living in a walkable neighborhood and prefer an idealized version of it to a suburban-home-with-long-commute scenario:

But of course we’d expect people to support it when that’s the pitch; there’s no downsides, it costs nothing, and you get to live in a cobblestone paradise built by Moses himself. I think this is probably the level at which most people understand walkability - it’s about the same level where communism sounds like a really neat idea. As you’d expect, this makes all my internal don’t-get-fooled alarms go off at once - I have a surprisingly strong adversarial response to the entire idea.

The next level of understanding is what I think of as the city-planning-and-real-estate level - it’s represented by things like the commercial-friendly Walk Score, which starts to formalize things the tiniest bit by looking at metrics like the distance from a particular address to places a person needs to visit regularly in their day-to-day life. At this level, walkability is almost entirely about logistics and math. If you can walk to a grocery store, your church or any other often-needed location in a reasonable amount of time everything is cool and your score goes up. The more you need a car to live your daily non-commute life, the lower your score is.

If Walk Score was as complex as walkability gets, I don’t think I’d be able to get an article out of walkability in the first place. But like a lot things, it doesn’t stop there; in the same way things like vegetarianism ramp up pretty quickly to more intense forms, walkability has both its casuals and its level 5 vegan ultra-enthusiasts. It’s these enthusiasts I want to focus in on, because with them you get a better picture of where unchecked walkability would choose to take us.

Becoming one with the Stroad

If you were the kind of giant nerd who gets into an argument about walkability with internet friends and then decided to revenge-research the subject to death, there’s a fairly high probability the first website you will run into is Strong Towns. Strong Towns is sort of a one-stop shop for articles and information on how to convince your local city planners of the superiority of narrow streets and European-looking plazas.

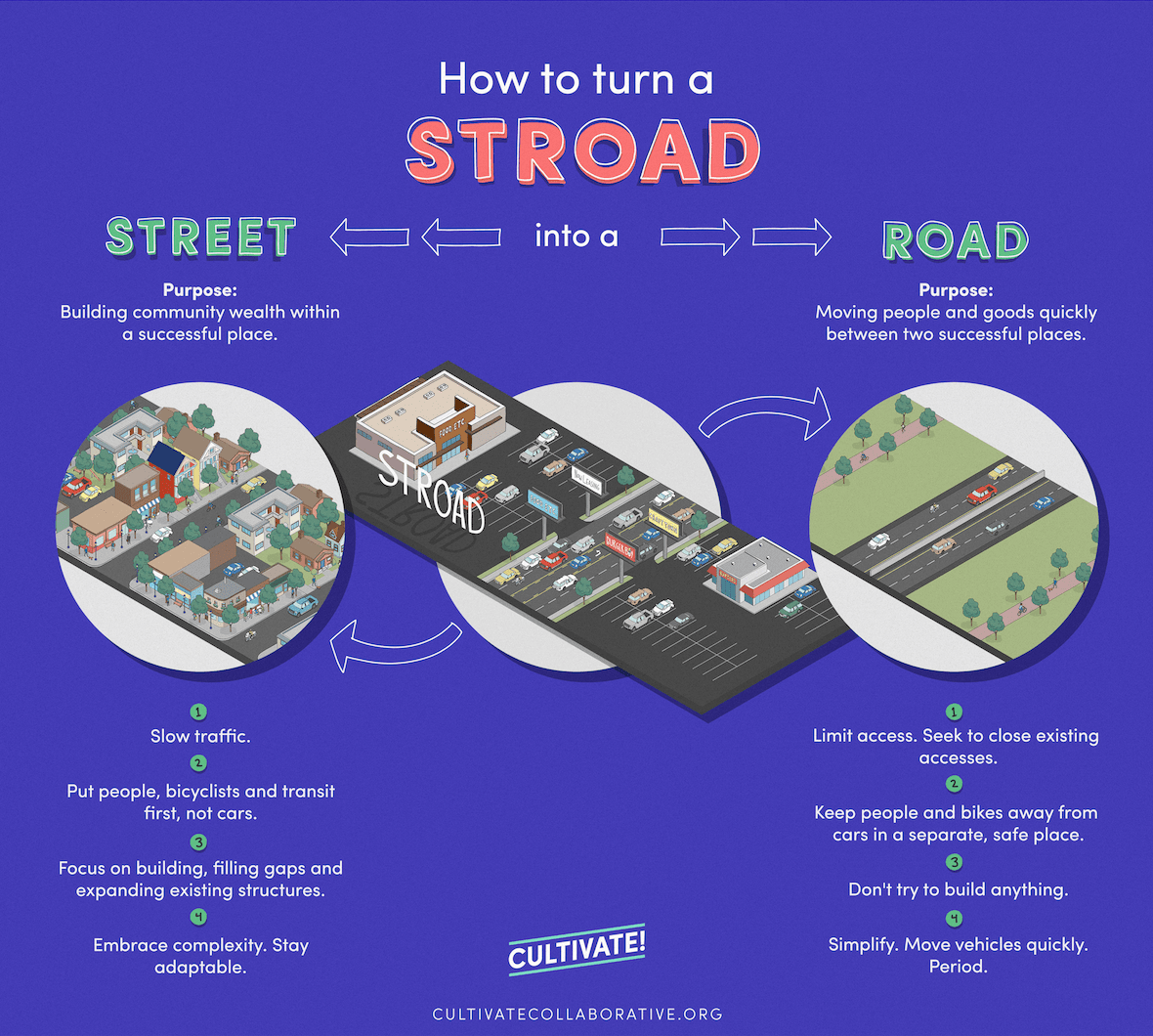

When I first started digging into walkability, a few friends (who may or may not end up annoyed with me for writing this) supplied articles from this source. One of the more prominent claims of the site, something that pops up again and again in different articles, is that the cardinal sin of modern city planning is something called a Stroad. There’s a very basic description of it here:

Back in 2013, Strong Towns coined a word (“stroad”) to describe the multilane thoroughfares that are dangerous and financially unproductive, yet somehow also ubiquitous in North America. The stroad is what you get when you try to combine a street with a road. Yes, there’s a difference. Streets are platforms for creating value and building wealth; with narrow streets and wide sidewalks, they’re designed for people. Roads are efficient connections designed to get you from one productive place to another; they’re designed to move cars fast. The stroad is something else altogether, a street-road hybrid. By trying to do two things at once, it does neither well, and Strong Towns president Chuck Marohn has described the stroad as “the futon of transportation”:

So a Stroad is a by-definition-bad combination of a street and a road, trying to do two things and failing at both. Strong Towns hates it, and consistently presents it as an unnatural thing of terror, something obviously and clearly to be avoided at all costs. Separating the two is, Strong Towns maintains, similar in that it’s clearly good - doing so would fix a lot of problems with absolutely no downsides they ever mention or acknowledge in any way.

It’s possible you didn’t know that the definition of street was so complex, included a bunch of commerce/wealth building sub-clauses, and that they are “designed for people” (as opposed to cars). You probably also didn’t know that a road had cars in its definition (Ancient Rome is also surprised). Don’t feel bad; I didn’t know either. If you - like me! - thought that a road was just something you travelled on and a street was a road inside a town, that’s because the dictionary definition of road and street are just as I said - Strong Towns made up the definitions it’s using here and pretends they are normal to try to sell the harder-to-swallow Stroad concept.

This odd attempt to mislead doesn’t mean they are wrong that Stroads suck, but it does mean we have to look closer at what they actually want. My experience is that if someone is weirdly obscuring things like basic definitions, they might be being weird about other stuff. But it’s surprisingly hard to pin them down to anything solid.

If you read that article I linked, you find that they argue a point like someone who never gets seriously challenged, making big, vague claims that demand a lot of action but don’t provide a lot of specifics in terms of support or desired direction (see: Kendi, Ibram). For instance, in the quote I provided they simultaneously claim that Stroads are bad at moving cars, but also that cars on Stroads move much too fast - these aren’t necessarily mutually exclusive, but the incongruity seems to require some level of explanation to mesh the two (like, maybe the streetlights are supposed to suck out all the extra speed, or something). Strong Towns hates putting those definitions in one place, so I went digging.

So first we need to know what a road really is to Strong Towns. We can start here, where they include this infographic and quote:

We should not allow extraneous accesses onto our roads. Intersections, on-ramps and exit ramps slow down traffic and artificially create congestion. Interchanges should be many miles apart and should focus on moving traffic, not facilitating development. We should not mine — or allow others to mine — the large public investment in roadway capacity for the short term economic gain of a few (i.e. those who live or work near the on- and off-ramps or intersections). That is what we are doing when we add accesses to our roads. We are stealing pennies from everyone and throwing most of them away while giving a handful to the adjacent land owners. It’s bankrupting us.

Where we anticipate, or desire, people outside of automobiles — walking, biking, etc. — we need to do that on separate facilities. There is no way to safely bike five or ten feet away from automobiles moving 40, 50 or 60+ miles per hour. The margin of error is unacceptably small. Biking and walking should be completely separated from a road.

The bolds there are mine. From the infographic and the quote, we’ve already been able to put together some rules:

Roads don’t have buildings next to them, or at least we shouldn’t build buildings next to them.

To get on a road, you might have to drive “many miles” to find an on-ramp; they are ideally intentionally difficult to access and exit.

Any “street” has a top speed (for now!) of 40 miles per hour - the quote says pedestrians should never be near a speed that high, so while we don’t know if Strong Towns would let a street go as fast as 40 MPH, we know it wouldn’t allow anything faster.

None of these rules are bad, but we have to look closer. For instance, that 40 MPH estimate gets adjusted downwards a lot when we look at our next article:

I advocate for a 20 mph speed limit, a number not based on pragmatic lobbying but on empirical evidence. I believe that, where such a speed limit is called for -- anywhere where we anticipate automobiles will be in the proximity of humans outside of a vehicle -- it is the responsibility of the engineer to design the street so that only a handful of deviants exceed the desired speed, a proportion of the population that can be dealt with through law enforcement.

How do engineers do this? They do it by making the street feel unsafe for the typical driver once their automobile exceeds the desired speed limit. Only when drivers feel as vulnerable as people walking and biking will our streets actually be safe.

So our streets are a little better defined now; they are at maximum 20 MPH zones with a bunch of speedbumps (or something) that make it very hard to drive faster than that on them. If you are me and you want to go places faster than school-zone speeds sometimes, that takes you to your next question - how does a Strong Towns approved pedestrian cross a Strong Towns approved road?

We already know one way; it can slow down to <20 MPH and become a street, at which point strong towns is OK with a crosswalk. But then it’s not a road anymore. The big, usable solution that pops to mind is pedestrian bridges, big raised walkways that route pedestrians over traffic instead of through it. They keep pedestrians well away from traffic, are safe, and don’t require traffic to slow from road-speeds to street-speeds. They allow for pedestrians and roads to co-exist in close proximity while not getting in each other’s way. They’d be perfect except for one thing: Strong Towns freaking hates them.

Most elaborate “pedestrian” infrastructure is really car infrastructure. As an example, let’s have a look at Lake Mary, Florida, a suburb of Orlando. Like much of suburban Florida, Lake Mary is a grid of multi-lane arterials. One of the city’s highest crash locations, according to its transportation plan, is the intersection of Lake Mary Boulevard and Country Club Road. Lake Mary Boulevard is seven lanes wide, with turn-lanes and through-traffic lanes, and is a daunting obstacle for pedestrians—so the city has constructed two pedestrian bridges over the highway, with a 153-foot span…

These elaborate and expensive pedestrian bridges are at best a remedial effort to minimize the danger this environment poses to anyone who isn’t in a car. They don’t really make the area any more desirable for walking. The real problem is not the infrastructure, or lack thereof, but a built environment that’s inhospitable to walking and cycling.

So you can’t cross a road with a crosswalk - it’s dangerous, because of the high speeds. And you can’t cross it in any safe way that’s slightly inconvenient for walkers, either. Later in that same article they reveal what they’d accept, which is (again) <20 MPH roads. You’d assume they’d also allow us to bury the roads, but this isn’t all that clear, and there’s no way in hell we could afford to do it nationwide anyway.

I had another thought - I live in Phoenix, Arizona. We have a lot of freeways. Strong Towns wouldn’t like them because you can get on and off them every mile or so, but they do have some things going for them: at every on-ramp and off-ramp in the metro area, the non-highway roads either go over or under the highway in a pretty seamless way. Essentially our freeways are “buried” for all intents and purposes. Would Strong Towns be OK with freeways with very, very limited entry and exit points?

No, of course they wouldn’t. But the reasons are very vague here and absolutely reek of hippy logic. For instance, freeways are bad because some guy can make them seem bad while playing a video game:

A Youtuber who goes by Donoteat is creating a fascinating series called Power, Politics & Planning that brilliantly uses Cities:Skylines as a storytelling tool. Subverting the tidy abstractions of this game and its genre, Donoteat uses the in-game graphics as a prop to reveal to us the messy, sometimes ugly human consequences of planning hubris that sees a city as a collection of roads and buildings.

Episode 2 is all about urban freeways, and to tell the story, Donoteat constructs a remarkably believable and richly rendered city whose rowhouse blocks bear more than a passing resemblance to Baltimore, Washington, or maybe Chicago. We watch as he plans a freeway which requires the demolition of a slice of this historic neighborhood—and then, as he clicks the button to remove each building condemned by eminent domain, tells us a bit about the life and fate of its inhabitant. These aren’t real stories, but they feel real—and might as well be. They begin to capture the gravity and the tragedy of the way freeways snuffed out the rich social fabric of real communities, consigned to the wrecking ball in the interest of speedy suburban commutes.

Or here, because they let people choose where to live and it turns out they don’t want to live in ultra-crowded city centers like Strong Towns-type urbanists prefer:

This simple fact, because of the rapidity of the change these freeways unleashed, had unimaginably destructive consequences for cities. The following series of stylized graphics shows what happened to dozens of metropolitan regions across the continent as a result of that first cataclysmic wave of urban freeway construction…

Every time a billion-dollar freeway or bridge project—or, yes, even a public transit project such as a rail line—is implemented, it changes the geography of access within its region, and may do so suddenly and destructively. Certain places become more convenient to live, work, and own property than before. Other places lose their comparative advantage.

Where we end up is that Strong Towns-type walkability people want a system where freeways are removed and all streets in a city are <20 MPH, except where no pedestrian might ever want to cross. For convenience, I’ve highlighted in sparkling, animated purple every place they would allow you to drive faster than 20 MPH in NYC:

If you didn’t catch the joke, there’s no highlighting there; there’s no place to put a road under that rule system. Same with Dallas:

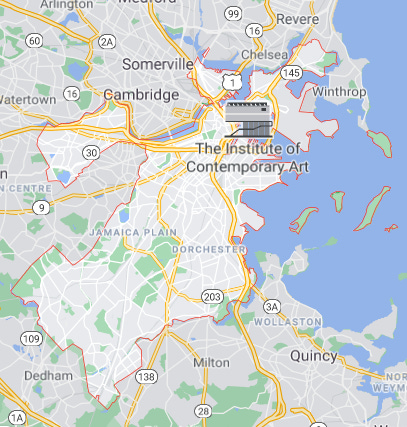

Or in Boston:

That’s all very snarky of me, but I think it’s called for here. These are people who want a very, very specific thing (all city traffic being limited to 20 MPH) and won’t say it. That’s likely because they want your support, but know they couldn’t get it if they told you what they actually want. It’s dishonest.

But Strong Towns trying to trick you doesn’t mean their ideas are de facto bad - they might be very good ideas that happens to be promoted by guys who don’t shoot all that straight. So next let’s examine what this kind of walkability actually costs - because it does cost something beyond the baked-in slow travel speeds.

You Have to Make it Up With Density, Prices, or Worse Stuff

Let’s say you like some kind of larger store - I’m rare in that I actually like Walmart, but I know most of you don’t. Let’s say you like some other big store of some kind, like REI or Costco; maybe you like a one-stop shop for trail needs or buying massive amounts of food all at once to save money. As of today, you can totally have those things because enough people can get to them to support them - that lends itself to all kinds of economies of scale, and you get more selection in one place for cheaper.

Or let’s say you want something really niche - say it’s a metal detector store, or a coffee shop entirely staffed by fitness models, or something. You can also have that (probably) because people can get to it; there might not be a lot of people that want any exact niche thing on your city block, but combining enough city blocks suddenly lets you have pinball machine dealers and dog-friendly ice-cream shops.

People don’t really think about “distance” in terms of distance - they think about it in terms of travel time. Dropping all town and city speed limits to <20 MPH makes these things farther away in the way that matters to people; that means less people live within a reasonable travel distance from any particular spot in the city. That means, all things the same, that you get less big-box stores and specialty shops.

One thing you can change that prevents this is price - if things are more expensive, a shop can support itself with less customers. But this is as close to a pure downside as you can get - it’s the same stuff, you are just paying more now. Or you could just do without those specialty stores and big-box stores, but that’s another clear-bad thing; you are just getting less utility and fun.

Strong Towns-type sites don’t really mention these downsides, but I don’t think that’s because they are trying hide them in this case. It’s more because their actual solution for this problem is something different: Density.

That Costco or your vegan cat cafe are theoretically viable even serving limited areas in a car-hostile world so long as those areas have sufficient population; this means more duplexes, fourplexes and apartment complexes; it means living a lot closer to a lot more people. Now, you may not like density (I absolutely hate it, more on this later) but it really would solve some of these problems - you don’t have to pay more for your stuff or have less of it, you just have to pack people together a little closer.

As you’d expect, Strong Towns’ takes on density are confusing:

Anyone who remotely comprehends the number of variables at play here would never ask such a ridiculous question. How valuable are the units? How well is the street maintained? What is the inflation rate for construction costs? What is the city’s bond rating? Will the association properly maintain the roof of the building? What will happen to the building across the street currently in probate? Does the city’s code empower NIMBY’s?

I could go on and on and on…. If density matters for anything, it is a byproduct of success, not its cause. And I’m not even sold on that.

That article is sort of down on density as a metric, saying it should be mostly ignored, but it’s not really saying it’s bad. This one seems to imply it’s good/necessary, but doesn’t come out and say it. I picked through a bunch of these, but couldn’t really pin them down to anything you’d call an opinion. That’s weird to me - again, you can’t limit access to stores and expect to have the same amount or quality of them a bigger customer base would support - but at least hide-what-you-want isn’t out of character here.

The Good Points Walkability Makes

I know this article has been really, really down on walkability so far. This is something I’m supposed to be careful of because, as you might have guessed, I hate housing density a great deal and downtown-lifestyles more. I have had the near-mythical experience of someone pooping on my stoop; I have had years of wandering drug addicts in the neighborhood causing trouble. I have had multiple bikes stolen and tent cities form within a half mile of my house. If this blogging thing ever takes off in a real way, I’m moving to the woods so fast my arrival will incinerate adjacent squirrels.

Worse, it’s been down on one particular brand of the thing. I want to make something really clear: I’m not actually against people being able to walk places, and I don’t want to weakman the whole movement with one variety of travelling-on-foot super-fans who really don’t like to clearly define their actual positions.

One thing that’s come up again and again in casual conversations with walkability friends that strikes me as fair are complaints about zoning restrictions. For instance, here’s an article about minimum lot sizes - in a lot of places, it’s illegal to build houses smaller than a certain size, which artificially limits density in places where it might make sense. I’ve heard similar things about minimum street widths, a situation in which mandatory rules making streets wider artificially limit density while also making traffic move faster through neighborhoods.

This seems like an easy win to hand to the Strong Towns people - I don’t think they should have carte blanche to do all the public anti-car initiatives they want, but that doesn’t mean they don’t have a legitimate grievance when the government restricts them from building certain ways on privately owned land. There are a lot of places where it makes sense to let the market decide, and this is one; if someone wants to build a walker’s utopia suburb, they should be able to, provided the market will support it.

(BIG NOTE: I’m about to mention a book, because the book as explained to me holds some concepts I think are relevant. I have not had the chance to read this book in its entirety. I’m working off summaries here, so if I misrepresent it that’s entirely my bad. With that being said, what I have seen of it is great.)

I recently had a great conversation1 prompted by an embarrassing misunderstanding that introduced me to some of the concepts in Alain Bertaud’s Order Without Design . The idea behind the book as represented to me is that the author looks at city infrastructure primarily as a method of moving labor towards labor markets - getting you from your house to your job. I was further told that what makes sense in that model is examining all land right down to each particular square meter in terms of its economic value, and making your decisions based off that - in some cases, it might make economic sense to tear down some parks to build some highways. In others, it might make sense to tear down the same highways to build high-rise buildings.

I’m not sure I agree with the ideas here whole-cloth; for one, I don’t know where something like a park would ever make sense in that model. The author might very well address this, but abstract economic ideas often don’t translate very well into the messy, un-abstract real world we live in. But it does tickle some of my more libertarian biases none-the-less.

I want to live in the suburbs and have the advantages of driving at reasonably high speeds, but that doesn’t mean everyone does. Some people want to live in super-dense urban environments, even if I don’t. I don’t want Strong Towns to be able to force me to drive everywhere at sub-bicycle speeds, but my general principles also demand that it’s equally wrong to ban them from building out individual areas that way, if they want and can use private-domain solutions to make that happen. This market approach even solves the problem of Strong Towns muddling the waters around their actual demands - let them build whatever; if it doesn’t work, the customers will let them know. I have a reader who builds self-contained communities where you don’t need a car - I actually love the idea, even if I don’t want to live there. And if enough people do want to live there, it will succeed. Simple as that.

For me, that’s the magic of revealed preference - so long as we don’t ban each other from doing what we wish, the economics of the thing usually work out such that we all end up with what we (collectively, in a distributed way) want.

OK, so this is sort of a great story. One of my readers is, as mentioned, an entrepreneur who builds self-contained communities designed in such a way that you don’t need a car. He was pinging me about a different article, and I mentioned I was writing this one; he was super excited about it, since walkability is one of his favorite subjects.

I sprung at the chance to ask him for a phone call to talk about the article, since I wanted some balance on it. He was down. We get on the phone and he’s giving me pure gold - he absolutely knows his shit, he’s giving me all this great perspective and I’m just learning a ton. And I tell him “I was actually going to mention you anyway, because of what you are building”. And he says “Wait, what?”

IT’S AN ENTIRELY DIFFERENT GUY. I have a lot of trouble with names; I can’t remember them most of the time. And their names are just similar that my brain scanned the email and went “Yup, same guy. Totally the same guy, no need to check or anything.”

Now, I feel very lucky to have had that phone conversation - the person I talked to was absolutely the expert I needed even if he wasn’t the expert I expected. But holy hell was I embarrassed. Dude, if you are reading this, you absolutely made this article better. Thank you so much.

(The gentleman in question didn’t want his name mentioned, but absolutely wanted to get the word out on his favorite book about city infrastructure, Order Without Design, which I linked to above).

Great piece. I appreciate the time it took to break down these arguments. That said, I am not sure that you picked the right target in Strong Towns, who are really not your typical New Urbanists. I suspect that your case against them has something to do with your aesthetic distaste for density and urban living. And that may be somewhat warranted, as lots of urbanism boosters foster a thinly veiled distaste for rural and suburban living. But again, I do not think that is what Strong Towns is going for. My reading of Strong Towns is not “cities good; everything else bad.” I don't even think that they are anti-car. Rather, I think that they are advocating a move from exurban sprawl to something resembling old-fashioned inner-ring suburbs and small towns with charming Main Streets.

The exurban sprawl issue is where the case against stroads comes in and it is a particularly confusing concept. Here is a pretty easy way to know if you are on a stroad. If you go down to the commercial district to run visit two stores that are exactly across from each other on opposite sides of the street/road, how would you get from the first to the second? If the answer is ‘walk across,’ then you are on a street. If the answer is ‘get in your car, drive away from your destination and find somewhere you can make a u-turn, then drive back and pull into the parking lot,’ then you are on a stroad.

Part of the reason why you cannot suss out a clear position on density is that they do not see density as something that ought to be determined or prescribed by policy. A place should be as dense as it needs to be to support the economic vitality and financial health of the place. One of Marohn’s big crusades is against the need for local governments to endlessly issue debt that it can never pay off. The reason that happens is because many of cities and towns have way more infrastructure than they can maintain given their tax base. This ties back to stroads, which require all the commercially viable businesses to be located over an unnecessarily large area, which necessitates more capex and more operating expenses, which make these places not economically viable in the long run.

You were right to start this with a discussion of preferences, but preferences are part of the problem. People want to live in nicer, more pleasant neighbourhoods than they can afford, so they try to mimic nicer locations with land-use regulations. That works for a while, but eventually the bills come due and the people with means have moved on to the next new housing development or shopping complex.

I'm very sympathetic to the demands of people who like walkability, although only to a certain extent - I cycle, and I much prefer wide roads that give cars plenty of room to pass to narrow roads where I accidentally back up traffic. I think the ideal situation was a town I once lived in called Stevenage in the UK, which had an elaborate network of underpasses that allowed cyclists and pedestrians to pretty much go anywhere in the town without having to cross roads. However, the entire place was built in the 1960s (and everyone hates it and thinks its ugly), so I don't think it's really practical to retrofit those into somewhere else.

I basically agree with you that the best solution is to have lots of different types of community to meet different needs, I think it makes sense to try to make city centres walkable since you're most of the way there already and that's usually what city people like, but you shouldn't forget that there's a need for access from outside the city. I do think the concept of having uncrossable roads is a really bad idea, it's nice to have pedestrian access for those times when its relevant.

I can kind of see what they're doing with the road/street distinction, the location does mean they have different connotations, but in my experience it can be very effective to have "roads" going through cities to separate traffic, as long as there's a way to go around them.